(Language ripples our lips)

– Susan Howe, “Pythagorean Silence”

the ground which is an absence of ground

– Michel Foucault, “Distance, Aspect, Origin”

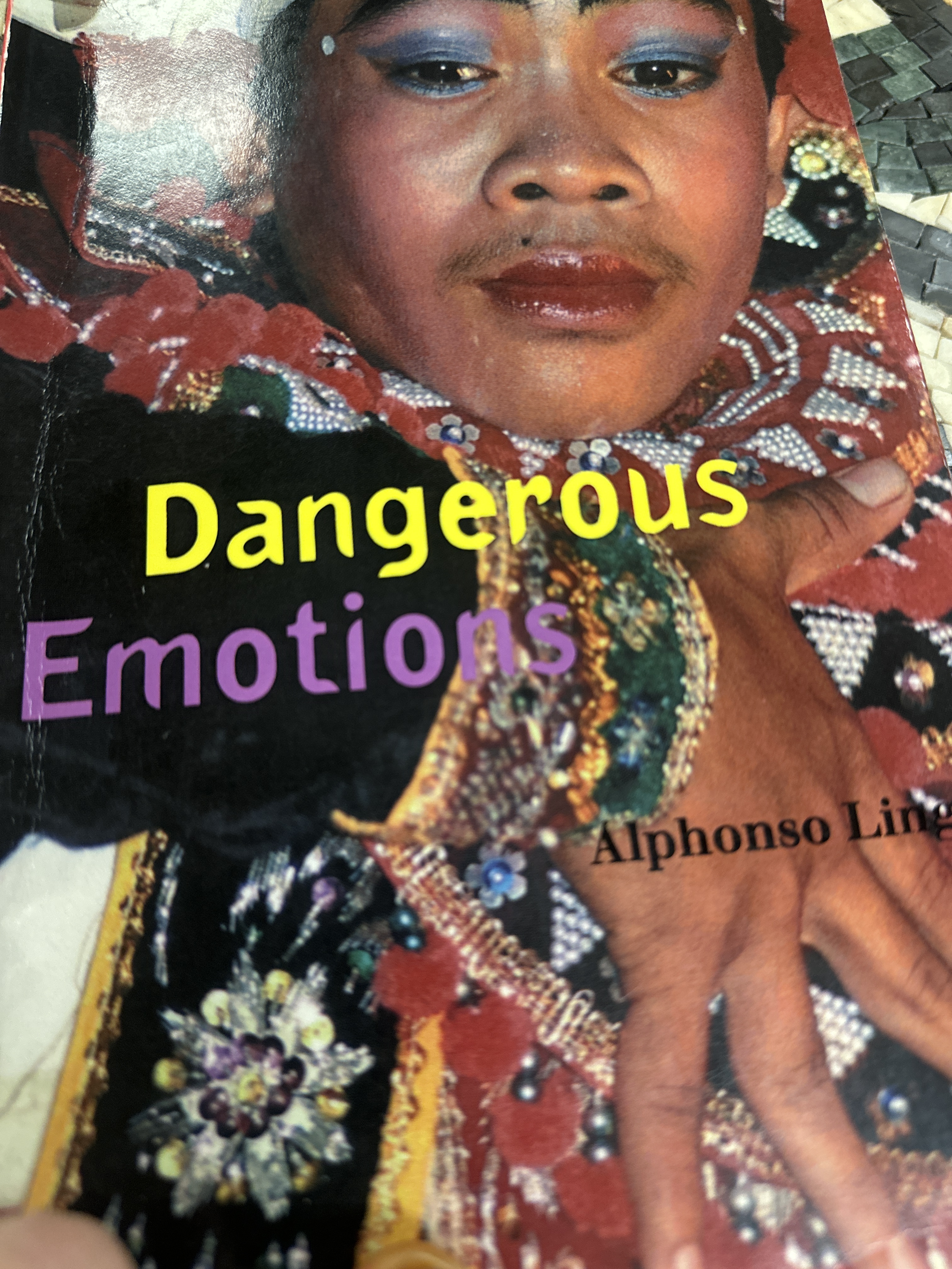

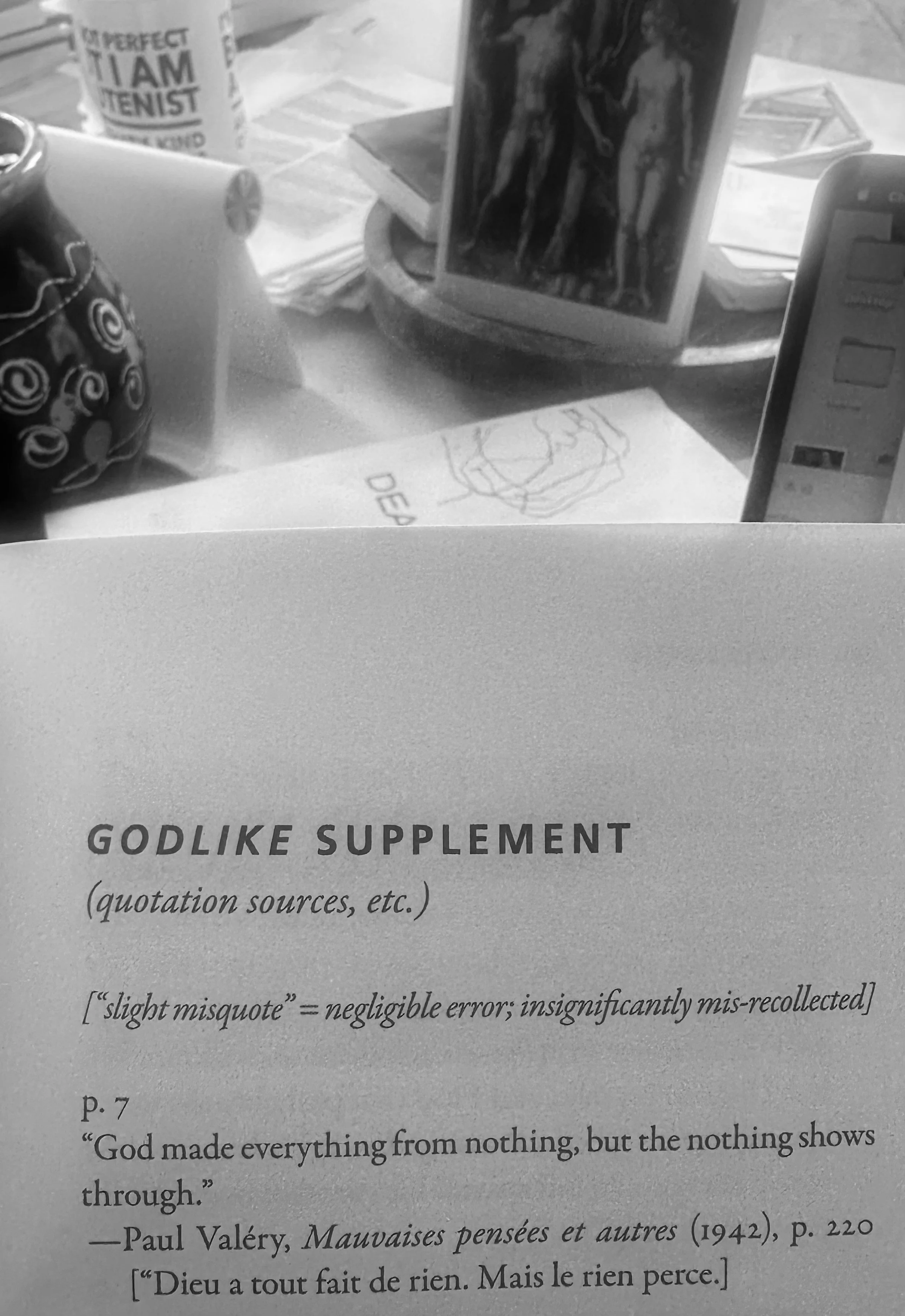

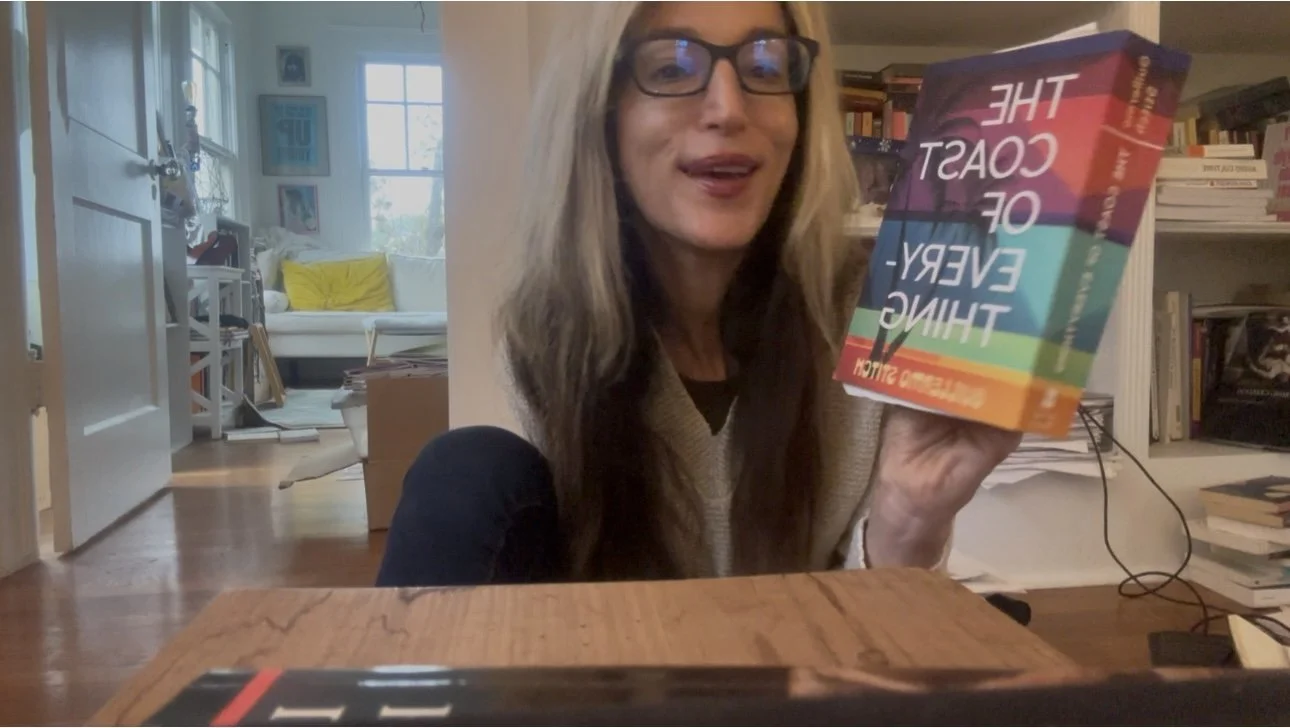

A few excerpts from this book by Alphonso Lingis that I am currently enjoying —

OF TORPOR AND SUBLIMITY

People who shut themselves off from the universe shut themselves up not in themselves but within the walls of their private property. They do not feel volcanic, oceanic, hyperborean, and celestial feelings, but only the torpor closed behind the doors of their apartment or suburban ranch house, the hysteria of the traffic, and the agitations of the currency on the stretch of turf they find for themselves on the twentieth floor of some multinational corporation building.

If one person regards a thunderstorm over the mountains or the ocean waves breaking against the cliffs as dangerous and another as sublime, the reason is not, as Immanuel Kant wrote, that the first clings to feeling the vulnerability of his small body, while the second initially verifies that his vantage point is safe and then forms the intellectual concept of infinity, which concept exalts his mind. And it is not simply, as Nietzsche wrote, that the first cramps his weak emotional energies back upon himself, resenting what threatens his security, while the second has a vitality whose excessive energies have to be released outside. It is that the first draws his emotional energies from the forces that hold walls together and closed.

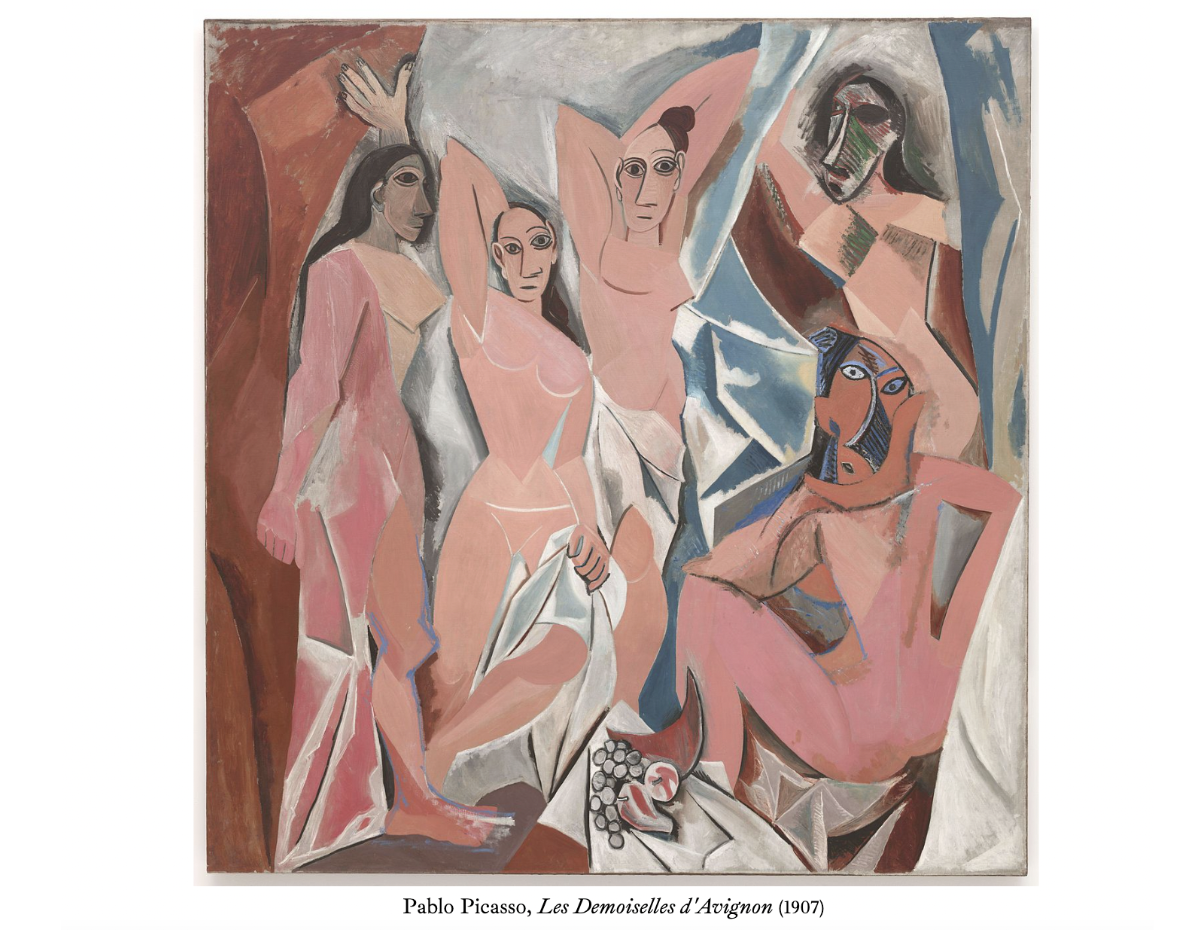

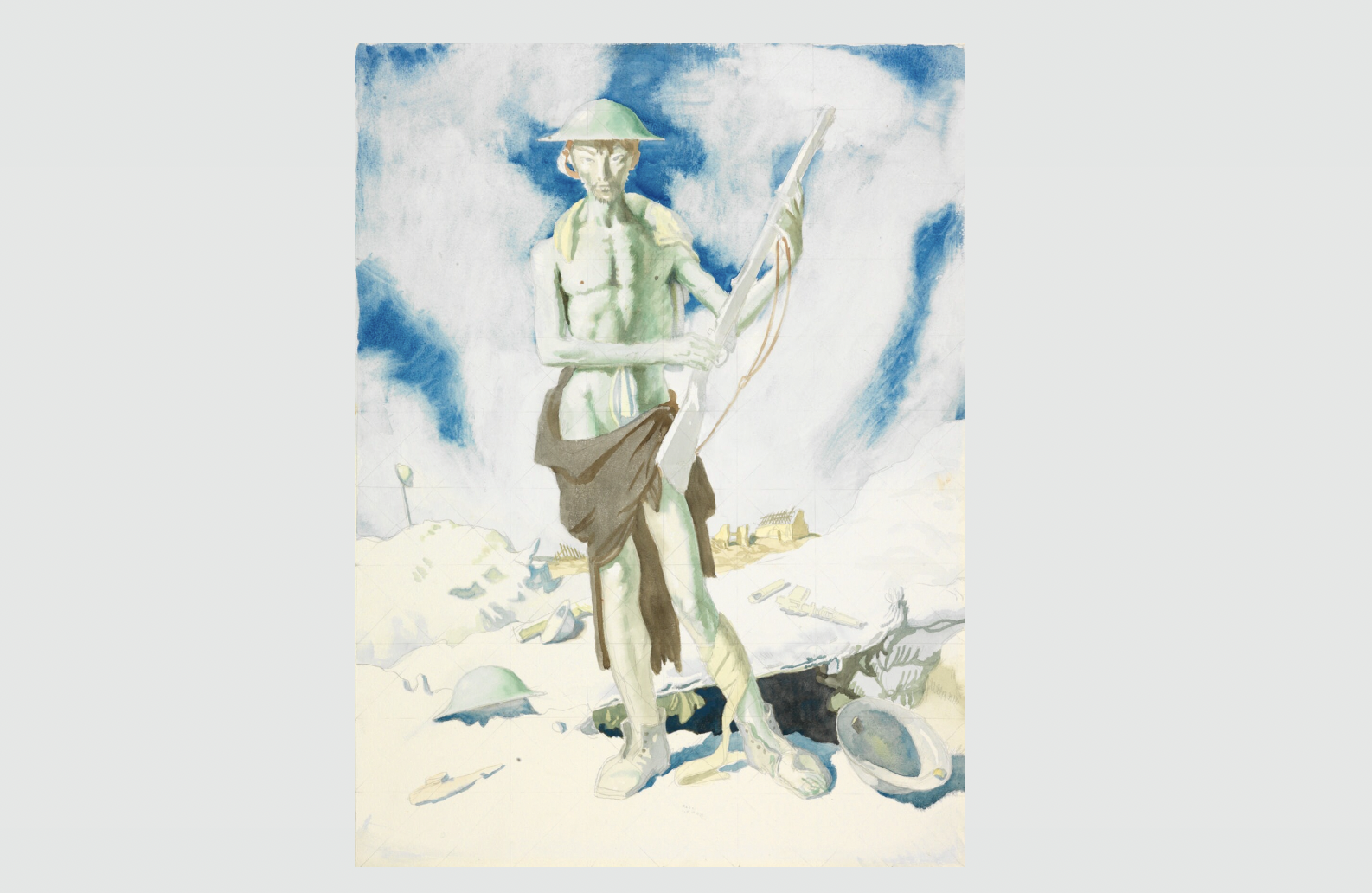

OF “GREAT” CIVILIZATIONS (AND GREATNESS AESTHETICS)

About halfway through grade school I brought up a linguistic problem to the teacher. She and the text-book called the Roman civilization a great civilization. It was said to be at its greatest when its military dominated the greatest number of lands and peoples. When its empire shrank, it was said to be in decline. This terminology persisted in history class after history class throughout my schooling, and in museum after museum I have visited since. The great religions are the world religions. Civilization advances with military and economic expansionism.

A euphemism is competition: without competition there is no artistic, literary, or religious advance. (Without grades, prizes, honors, there is no philosophical achievement.) My first trip was to Florence, where I was beset by the evidence that its grand artistic, literary, and musical achievements coincided with its richest and most rapacious century . . .

OF ANEMONES AND US

Sea anemones are animated chrysanthemums made of tentacles. Without sense organs, without a nervous system, they are all skin, with but one orifice that serves as mouth, anus, and vagina. Inside, their skin contains little marshes of algae, ocean plantlets of a species that has come to live only in them. The tentacles of the anemone place inside the orifice bits of floating nourishment, but the anemone cannot absorb them until they are first broken down by its inner algae garden. When did those algae cease to live in the open ocean and come to live inside sea anemones?

Hermit crabs do not secrete shells for themselves but instead lodge their bodies in the shells they find vacated by the death of other crustaceans. The shells of one species of hermit crab are covered with a species of sea anemone. The tentacles of the sea anemones grab the scraps the crab tears loose when it eats. The sea anemones protect the crab from predator octopods, which are very sensitive to sea anemone stings. When the hermit crab outgrows its shell, it locates another empty one. The sea anemones then leave the old shell and go to attach themselves onto the new one. The crab waits. How do sea anemones, blind, without sense organs, know it is time to move?

How myopic is the notion that a form is the principle of individuation, or that a substance occupying a place to the exclusion of other substances makes an individual, or that the inner organization, or the self-positing identity of a subject is an entity's principle of individuation! A season, a summer, a wind, a fog, a swarm, an intensity of white at high noon have perfect individuality, though they are neither substances nor subjects. The climate, the wind, a season have a nature and an individuality no different from the bodies that populate them, follow them, sleep and awaken in them.

Let us liberate ourselves from the notion that our body is constituted by the form that makes it an object of observation and manipulation for an outside observer!

Let us dissolve the conceptual crust that holds it as a subsisting substance. Let us turn away from the anatomical and physiological mirrors that project it before us as a set of organs and a set of biological or pragmatic functions.

Let us see through the simplemindedness that conceives of the activities of its parts as functionally integrated and conceives it as a discrete unit of life. Let us cease to identify our body with the grammatical concept of a subject or the juridical concept of a subject of decisions and initiatives.

The form and the substance of our bodies are not clay shaped by Jehovah and then driven by his breath; they are coral reefs full of polyps, sponges, gorgonians . . . A pack of wolves, a cacophonous assemblage of starlings in a maple tree when evening falls, a marsh throbbing with frogs, a whole night fizzling with fireflies exert a primal fascination on us. What is fascinated is the multiplicity in us— the human form and the nonhuman, vertebrate and invertebrate, animal and vegetable, the conscious and unconscious movements and intensities in us.

(Italics are mine.)

*

Alphonso Lingis, Dangerous Emotions (University of California Press)

Arnold Schoenberg, Notturno for Strings and Harp (1895-96)

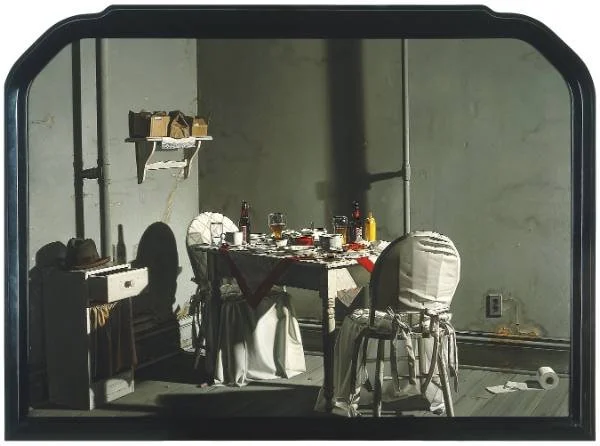

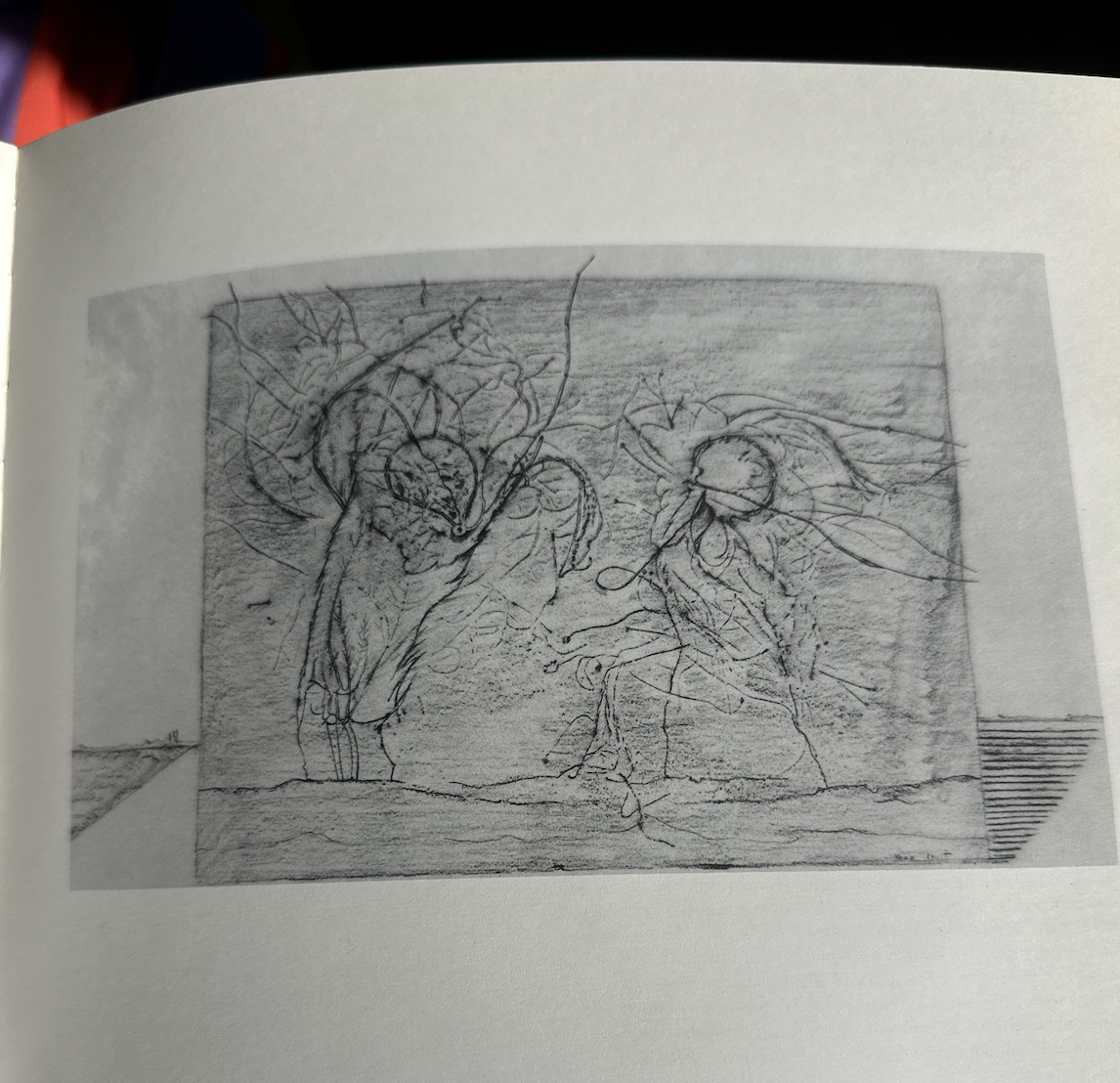

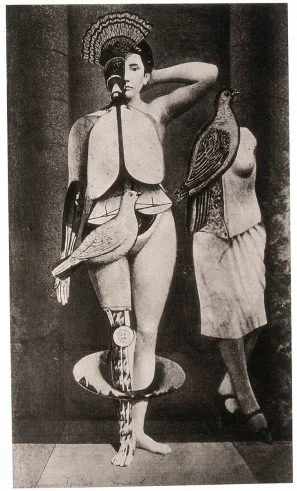

Eugène Delacroix, The Duke of Orleans showing his Lover, ca. 1825 - 1826