1. The dog in the room

My head was whirring today—-everything blurred inside it. So I sat with my youngest child, who was busy making collages of our dog, Radu, from old literary magazines. Something about the wordy dogs she created made me think about language, about shapes, about fragments and vessels and colors and detritus.

The anxiety of a prior day's drafts, the loom of deadlines, the paralysis of procrastination—these are not unusual in the writing life. One way to move past them is to enter the work (and subject) sideways through collage, using the peripheral vision or sidereal eye in writing, staring less at the subject than into the space around it.

Collage is a vehicle that helps reveal the nonlinear. And nonlinearity is poetry’s starter fluid.

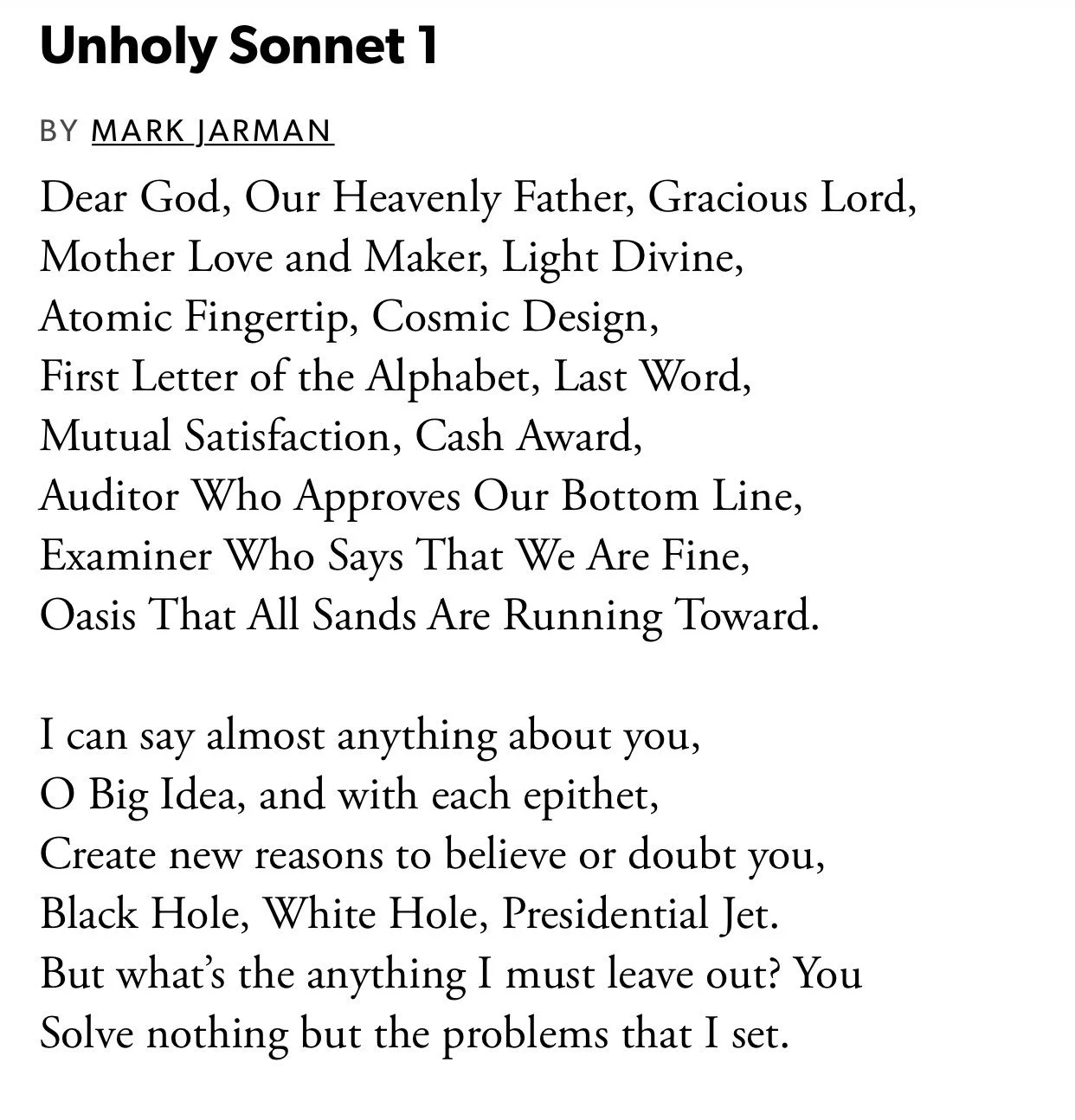

2. Mark Jarman’s “Unholy Sonnet 1”

To inventory in a nonlinear way—this is also how the collage works in a poem. A list that doesn’t need to be read in order to mean something. A cloud of images collated from other places, whether the mouths of others or folksay.

Mark Jarman’s “Unholy Sonnet 1” makes the reader aware of its constraint from the outset: we know this will be a sonnet. Beyond that, it cuts and pastes, or inventories the names for God.

So we have a simple white paper background, or a material basis that doesn’t want attention. (A sonnet seeks to blend itself into the poetry landscape; it uses the field in a manner that accords with out expectations.) What Jarman does is bring a mixed diction, a blurring of holy and profane, into the poem.

3. Staring at a collage can generate poetry

This is just another way of saying that collages make me want to write. The layers and juxtapositions—-the fragmented nature of the visual encounter—-can lead to ekphrastic poetry, whether one acknowledges the ekphrasis or wanders off into a different imagined space.

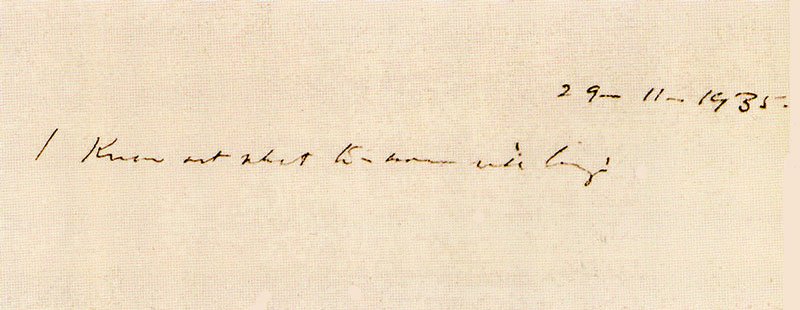

There is a woman on his hand….

Joel-Peter Witkin, Le France et le Monde, 2011.

4. Collage unsettles the distinction between uses and abuses

Collage can be used as a discursive tool to prompt conversation—or extend existing conversations in uncanny ways— as well as a subversive tool which undoes the settled object relations in our minds.

Like a poem, the composition of a collage depends on its entirety, or the whole. Working too closely distorts the view and foregrounds the parts over the whole.

In both poetry and college, I think the best view is one that alternates between moving up very closing and stepping back, up close and then back, again and again, until both the whole and the parts are radiant.

5. Max Erst is a must for every writer’s notebook

I save collages and illustrations by Ernst on my desktop to needle me towards unusual words and images.

Max Ernst, Approaching Puberty… (ThePleiades), 1921.

5. PICTORIAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY: a collage exercise

For this, you will need a print-out of a comic triptych with three panels. You will also need a glue stick, some magazines, scissors, and colored pencils (optional).

Once you have your materials, draft three collages in cartoon-like triptych. Each panel should depict the following phases: 1) childhood 2) teen years or adolescence 3) adulthood. Flip through the old magazines for ideas. Consider how you could represent yourself symbolically as a character, a chair, or a fox or maybe a cockroach. Let the images and materials in the old magazines shape how you tell the story of your life.

Georges Hugnet, Mademoiselle Lachèvre, 1947.

6. DIRECTED COLLAGE: a collage exercise

Assemble the following materials (piece of cardstock paper or old cardboard; colored pencils, old magazines, scissors, glue stick, acrylic paints or watercolor, paintbrushes) and then follow instructions without thinking too hard about why you're doing what you're doing – go-with-the-flow – work fast; go by instinct.

Use a large paint brush to cover one half of the page with the paint color of your choice.

On the unpainted side, use a colored pencil to scribble the names of 24 people in your life who were important or significant, however you choose to define that.

Tear a number out of a magazine & glue it to page. Add another number near a name.

Find the following and tear and glue them: an animal, a vessel, a form of motion.

Pick up yr black or dark paint. Just hold it for a second. Now put it down. Put it down.

Rip out an image of a map or a diagram from a magazine and glue it on the opposite corner from the animal. When I say rip, I don't mean cut with clean edges; I mean remove with the hand in a way that reflects the imperfection of borders when we try to remove anything by force.

Text your ex. Or pretend to text your ex. Don't text your mom. Don't text your mom's ex.

Keep working. Push yourself to the limit even if you feel lost. Find ways to evoke or create relationships between those names. Paint over some of them in light paint, if you want. Use colored pencils to connect or displace.

7. Additional collage techniques to enact slippage between subjects

Dropping spots of bleach onto tissue paper with an eyedropper allows white to bulge, creep, and contaminate the material in unpredictable ways.

Using tissue paper as paint—think of stained glass windows, and how the layers of glass create new hues in relation to light.

Bleeding colors at the border of tissue paper resemble the shoreline on a map.

Crumpled and flattened tissue paper in the collage translates the wrinkles into slender traceries. It can be used as an overlay, or an underlay.

Small sraps of paper scribbled with pastels or watercolor paints are also fragments that can be added to unsettle or alter the collage.

Old maps and tourism brochures, wallpaper samples, trash, fabrics cut to the shape of buildings or flowers, inventory of bird beaks, thesaurus entries, diagrams from a science magazine, the shape of people dancing cut from maps and bombed buildings, tourism brochures.

A splash of coffee or wine.

Scribbling over the paper with wax crayons or with a candle before painting over it and watercolor adds texture, creates a sort of ghost writing in the background.

Always consider the contrast, the juxtaposition, the brushstrokes. Move by deformation.

Noah Davis, Frogs, 2011.

8. Collage Paste Recipe (vs. glue stick)

If you’d like to make larger collages, there is a certain paste that people create for this purpose. You need a bowl and some white Elmers glue and a brush. Dilute the white glue with water until it has the consistency of milk, then brush it on the back of the paper and also on the surface. This diluted glue brushed over tissue paper creates texture, like a layer which absorbs light, adding density. Unlike a glue stick, the glue paste enables you to paint over the various objects and layer from above (rather than underneath, which is how we use the glue stick).

Babi Badalov, Schizopoetry collage

9. Assemblage

An assemblage is simply a collage made with 3-D objects rather than fabric or paper.

Tate Museum traces assemblage back to Pablo Picasso’s cubist constructions, the three dimensional works he began to make from 1912. An early example is his Still Life 1914 which is made from scraps of wood and a length of tablecloth fringing, glued together and painted.

But Dadaists (and Surrealists) made the most interesting use of assemblage, in my opinion. Kurt Schwitters’ “merz” technique relied on scavenged scrap materials from the streets themselves, from dumpsters and trashcans. It was degenerate in the most controversial sense of the word.

In David Lynch’s assemblage, the golden frame evokes a sort of childhood nostaglia for framed family portraits—and Lynch makes use of this frame to unsettle the ordinary. The juxtapositions create the associative language, and the nightmare grows from these associations.

10. Zine Folding

Since much of this play came to me while prepapring for Zine workshop sponsored by Sarabande Books, I wanted also to share their video for how to fold a simple zine from a sheet of regular paper, and to consider how this can be used as a medium for collage as well.