Shelley Wong. As She Appears. YesYes Books, May 10, 2022

Cover & Interior Design: Alban Fischer

81 pages, ISBN 978-1-936919-5

Winner of the 2019 Pamet River Prize

*

Anne Carson once wrote that “eros is a noun which acts everywhere like a verb”. . . There is a stickiness to eros, and it is the stickiness that made Jean Paul Sartre cringe in Being and Nothingness. For Sartre, "viscosity" is a repellent "state halfway between solid and liquid… unstable but it does not flow," electing to cling like "a leech" which attacks "the boundary between myself and I."

The viscous is sticky, unlike water which allows Sartre to stay “solid” when swimming in it.

"To touch stickiness is to risk diluting myself into viscosity," Sartre writes, he then compares to "a possessive dog or mistress." Honey must have been horrifying to Sartre.

I thought of this viscosity, this sweetness, when reading Shelley Wong’s first poetry collection, As She Appears.

I marveled at how Wong creates an erotic palette of soft colors and vowels which feels viscous without being possessive. As a queer Chinese-American poet, she palpates the stickiness of hybridity and personhood while queering the gaze, and playing with the lens to highlight how the self is seen— how being seen over-determines being, itself. Or her-self.

Wong’s voice carefully unpacks the silences of love; she aims "to tell all the quiet sisters" to whom this poetry collection is inscribed. In so doing, Wong "talks" about the weather — each of the book's four numerated sections ends with a "forecast" poem which subverts the reading of future weather by bringing climate to bear on expectation . . . And so we move with the poet through the seasons of a relationship, but also a life.

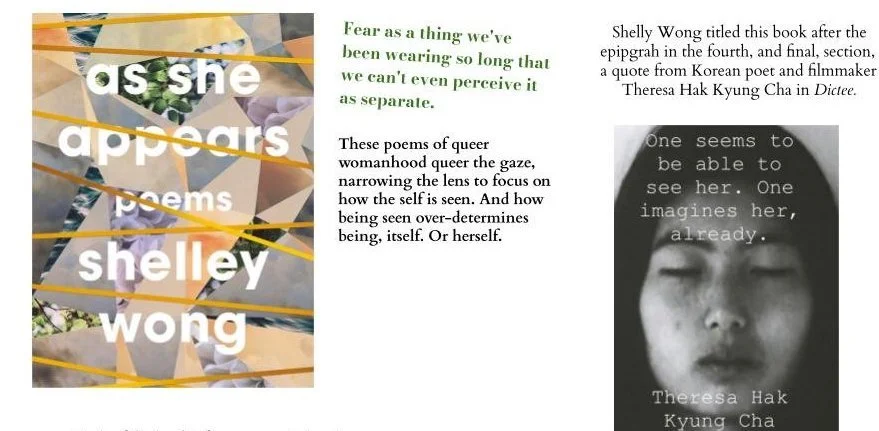

Only one of the sections has its own epigraph,namely, the fourth section, the last one before the Coda. This epigraph from Korean poet and filmmaker Theresa Hak Kyung Cha's Dictee also titles the book:

One seems to be able to see her. One imagines her already.

Looking at Each Other Across Seasons

Muriel Rukeyser’s poem, “Looking At Each Other,” is set as an overaching epigraph for the entire book. “Yes were were looking at each other,” Rukeyeser confirms in this poem which builds from a place of confirmations and affirmations, a record and inventory of particular Yes's.

Yes, our bodies entire saw each other

Yes, it was beginning in each

Yes, it threw waves across our lives

Yes, the pulses were becoming very strong

Yes, the beating became very delicate

Yes, the calling the arousal

Yes, the arriving the coming

Yes, there it was for both entire

Yes, we were looking at each other

Summer, the season of warm nights and long-limbed light, is the first section. "The Summer Forecast" opens with a question about display:

Is it too late to go off-

the-shoulder?

Enjambment plays with fashion as an interpretive lens for subtle emotional display. There is a lover who takes photographs, and the speaker’s relationship to posing mingles with the apprehension of being defined by the lover’s lens. Flowers are everything in Wong’s book—the speaker's relationship to the flowers is a means of emotional expression, or forecast. I sensed this in the precision of her attention to the peonies, in a series of brisk couplets which close with an image, an act:

as I approached

softness with sheers.

The centrality of looking is also emphasized by the multiple ekphrastic poems. "Private Collection" uses the act of viewing art as a sort of erotic ekphrasis, and it is the quietness of the speaker which is conveyed in both aural and physical ways:

We wore quiet glasses, our hair in low ponytail

like George Washington.

The lover takes photos of the speaker looking away, and one senses a relationship morphing into a film reel. But there is also humor, a wry smile which exists as subtext, or as a correlate of the silence. You can see me without seeing me, Wong’s speaker suggests.

Topography and terrain also invoke silence, as in "Department of the Interior," written from Fire Island, where the speaker returns "in the silence that follows / a separation." Here, the barrier island feels like a loose metaphor for time's relationship to gravity and tides and the human body.

I love how the body is asserted in the fluidity of improvised language, as Wong reveals “For the Living in the New World”:

I may be happiest

improvising the language a body can make

on a dance floor. We are just learning

how female birds sing in the tropics.

Spring insists we can build the world

around us again. How has love brought you

here? My head is heavy from the crown.

Again, some part of amatanormative conventions are challenged by both the ornaments (i.e. the crown) and the seasons, or the expectations built into them by our relationship to seasons past. Spring brings green and renewal — or does it bring fire? How much of what we know can be relied upon to understand the future?

As a fourth-generation Chinese-American, Wong writes from a longing to know, or be known by, her homeland. This feels different from seeking to reclaim an identity —- perhaps it aims closer to seeking a living connection.

"To Yellow" is about race, and the direct address to the word emerges as a soft, gleeful rejection of being identified:

Dear yellow, you

have never covered my body.

I leave your light in the dark.

Embracing the relationship between light and what it touches, the poet gives yellow a particular power, and leaves the reader with a small epiphany:

how quiet

is strong & often beautiful.

Wong engages her heritage by moving around it, adding layers, as in "All Beyonce's and Lucy Lius" where it is tendered as a sort of social currency, or a set of instructions one can know without being known by:

I can't tell Mandarin

from Cantonese

drink hot water

"Refrain" bids adieu to "romantic sacrifice" when the speaker declares "I choose myself." Here, the self is posed against the duties of romantic love, where vows resemble "a closed hand," and flourishing occurs outside the promise, on the outskirts of the hot seasons.

Source: YesYes Books website

"I paint myself because I am alive," Frida Kahlo wrote in her diary. "I am the subject I know best."

Prior to this book, Wong published a chapbook on Frida Kahlo (Rare Birds, Diode Editions, 2017), and there are several Frida-facing poems in this collection.

In "Invitation with Dirty Hands," Frida Kahlo is the poem’s speaker who invites the "happy skeleton" to dance with her. Flowers, again, consecrate the space of heritage, or inheritance, as marigolds attach themselves to her "bloodline. Their soft throats crowd closer."

The epistolary "Dear Frida" begins by crediting Kahlo with the author's fascination with "flower names." Frida is addressed outside the shadow of her famous lover, Diego Rivera (Wong's decision to leave his name out of text seems significant), whose machismo the poet invokes:

He approves of your dresses

when your skirts unfurl

into a temple.

And there is "his first against" Kahlo's "locked door". The speaker references her own lover, and the quietude, the "desperate wanderings" her lover undertook; one senses a parallel between Kahlo and the speaker in the "quiet interior."

The "Epithalamium" written for Kahlo again gestures towards her marriage to Rivera, as well as Kahlo's bisexuality. But Wong subverts the epithalamium form by arming the betrothed rather than celebrating the wedding. It begins:

Lady, keep the tequila

by your lamp for when

you need a knife.

The instructions on how to make birds from azul paint to "wash away / the memory of his sweat, / the drowning taste" reinterprets Kahlo's art in light of her traumatic relationship with Rivera. Like Kahlo, Wong speaks in colors, borrows hues, builds a world from observation and affinity. The speaker admits:

I, too, worshipped beauty,

parading in my pastels.

I fought & I loved the silences.

The pastel peacock is remarkable, memorable counterpoint to the brilliantly-feathered male peacock with his palette of turquoise and deep greens and blues and golds while the peahens sit peacefully in their quiet creams and soft browns.

The poem "Albino" opens as a metaphor and then alters it at the end—the speaker is not quiet a pea-hen but rather a modified, pastel peacock.

“Serene Chinese hibiscus”": Wong’s playful representations

Towards the end of the book, the poems recreate the dislocation of pandemic time, or the way in which it alters the seasons.

The final forecast poem beckons spring, naming the flowers as "my queens of color," creating a relationship between the flora and the flesh:

Sandal

ready. A pointed foot.

Again, Wong emphasizes listening, and how words recreate or misanticipate us.

There is a Coda, a single poem titled "Pandemic Spring" where "color becomes a feeling," and blooms stand in for emotions: : the "shocked orange poppies" and "serene Chinese hibiscus." The coda seems to defy all prior forecasts; the speaker calls herself "a pastel queen" whose time is now measured by listening, measured and made and marked by the hum of memories in amid cherry trees. Italics designate the quotations which refer to the speaker without quite seeing her:

Along the secret lake, I linger under a cherry tree in full blossom,

as is my ancestral right, something my Ohio

friend once said to me about hunting. When the petals fall like

snow, I think all my karaoke dreams.

I love these echos, and Wong’s use of italics to create an interior dialogue which brings the voices of others into the mind of the poet, which is also the room of the poem.

Perhaps an entire book, or a year of seasons, throbs in the final lines of this poem, in the queer Chinese-American who has dressed herself in pastel pink to look back, to hug the redwood tree of her California home, and to speak plainly:

Dear ancestor: I am always rapidly departing, forgive me. To live, I want to be known &

loved, the two together, inseparable.

A beautiful book — sticky as the fondest hell, sweet as warm honey drizzled over yogurt, witty as quietude, and certain to have terrified poor old Sartre. What could be more delicious?