1. 1

“The future, the word, and the unknown are . . . linked. Words which consciously aspire to the future are heightened by the desire to rise, be free of, the tyranny of history.”

- Fanny Howe

“Oh! kangaroos, sequins, chocolate sodas!”

- Frank O'Hara

“Bodies have their own light which they consume to live: they burn, they are not lit from the outside.”

- Egon Schiele

Egon Schiele, in one of his many self-portraits. The frame of the sonnet is so tight somehow, so pre-drafted, that it makes a lovely vehicle for the self-portait. Or for a series of self-portraits.

I A. Richards defined poetic tone as the speaker's attitude to the listener. The tone of Schiele’s self-portraits is uniquely brutal. Ornately brutal—brutalesque. Like Tomaz Salamun’s “Status Sonnet”… The way the poem or painting uses its sequins.

1 . 2

One can’t do justice to the contemporary American sonnet in four Sundays, but one must try anyway—-as one must also share the notes of admiration which exist in the margins of one’s preparations. Of relevance: the perfect pro-rhyme position as articulated in “Presto Manifesto” by A. E. Stallings. For background on the 18th century sonnet, a book chapter. For sheer beauty, see Monica Youn’s breakdown of the Petrarchan sonnet and Milton in this excerpt from Blackacre. For sonic and structural subversions, see Candace Williams’ “Gutting the Sonnet: A Conversation with Jericho Brown” and Stephen Kampa's thoughts on "disguised form" and "echo verse" sonnets. For details on turns and motions, see Michelle Boisseau’s “The Dancer’s Glance” and Virginia Bell’s “The Turn as Poetic Striptease in Anne Carson’s ‘Wildly Constant’.” For a close look at Gerald Manley Hopkins and the curtal sonnet, see Haj Ross’s "How Hopkins Pied It". For anything and everything, see Mike Theune’s labor of love: Voltage.

1. 3

The texture of Anne Boyer’s archival sonnet notates itself in demise, as something which perishes and can (at best) be preserved. One thinks of the 19th century Atheneum group’s desire to manufacture ruins, or to create the ruined form of the substantial and monumental.

A Sonnet from the Archive of Love's Failures, Volumes 1-3.5 Million

by Anne Boyer

If you were once inside my circle of love

and from this circle are now excluded,

and all my love's citizens I love more than you,

if you were once my lover but I've stopped

letting you, what is the view from outside

my love's limit? Does my love's interior emit

upward and cut into night? Do my charms,

investigations, and illnesses issue to the dark

that circles my circle? Do they bother

your sleep? And if you were once my friend

and are now my villainous foe, what stories

do you tell about how stupid those days

when I cared for you? Because I tell stories

of how you must tremble at my love's terrible walls,

how the memory of its interior you must always be eroding.

The poem begins in the conditional— “If you were once inside my circle of love”— and sets this part as a single-line stanza so the reverb can reach down into each stanza separately. The stone-swoon internal rhymes of the second stanza, after the sharp enjambment—“my love’s limit? Does my love’s interior emit” —- reveals how splendidly the shorn word makes for a rhyme. It’s as if the limit got clipped, a bit of Samson and Delilah energy.

Kevin McFadden on sonnet: it has the "dramaturge's urges, it wants to talk itself out..." One feels this dramaturgical urge in the questioning of Boyer’s sonnet, in the trembling of “love’s terrible walls.” Ruination is the point as well as the momentum.

1. 4

Will teach Bernadette Mayer’s “Sonnet”—- every time I re-read it, the sonnet rises from the ruins of a skyscraper, insisting on being seen while forsaking everything except the patina of its form. But there is a building, and there are techniques which helped create it. Among Mayer's plays, notice the mixed references to pop culture near ancient history— G. I. Joe and Cobra Commander nestle near Catullus. Mayer does this with diction as well, so we have the high of "soporific" and the low of "fucking." Another play involves using found language— "to _____, turn to page___" comes from Choose Your Own Adventure books as well as women's magazines and instructionals. The Choose-Your-Own-Adventure vibe of the extra couplet is as modern as a sonnet can get. It's as if Mayer wants to suggest the sonnet of the present advertises a choice rather than a conclusion or an argument. It ends in an option. Or the illusion of an option.

1. 5

Voltas. The volt. The surge or the bolt. The position from one which one can pivot. William Matthews named it the “invisible hinge” in his poem, “Merida, 1969”, where a major change in content (or form) occurs across a stanza break. The poem doesn’t comment on the shift but absorbs it. Also called a “pivot” or a “dovetail joint.” Forrest Gander calls the volta the "argument turn." H. L. Hix has 12 questions about the turn.

1. 6

“Language is just music without the full instrumentation,” says Terrance Hayes. The musicality of the sonnet, particularly in the Petrarchan’s relation to be written for singing and scoring. Sonnet as a form which invites the imagined symphony into the texture. Instrumentation is figurative language and figuration, I think. One can bring various instruments into the poem, and maybe this is a more interesting way of thinking about “voice” in poetry—-or in the voices brought into a poem. The association of voice with Iowa-style, US ‘confessional’ poetry makes it difficult to discuss the vocable and vocalizations of poems: everyone presumes the voice is personal, and that they are developing their voice?

Elsewhere, Hayes on wearing multiple shoes and taking multiple paths:

“I have very little interest in establishing a fixed style or subject matter.… I’m very interested in wearing Larry Levis on one foot and Harryette Mullen on the other. Or on another day—in another poem—Gwendolyn Brooks and Frank O’Hara. Reading provides an infinite number of shoes and paths.” (Italics mine)

1. 7

American Sonnet for the Magic Apples

by Terence Hayes

Or the one drunken half-quarter grand uncle recalling

The sound speckled apples on his fabled real daddy’s

Coastal orchard made falling multidimensionally

To the vaguely salty combination of plantation dirt

And marshland bearing the roots of this strange

Distant cousin to the plum, the Cherokee palm tree,

And West African pear, color of a bloody, dusky, ruby,

Husky & almost as bulky as the lamenting lamb’s head

His daddy lopped off once & kicked at him laughing,

The uncle informed me wistfully at a reunion of family

Fleecers, fabricators, fairy tellers & makeup artists

With his cast-off awful alcohol stench burning my nostrils

As he gripped the back of my head & gazed deeply

At the speckled invisible apple or head in his hand.

The specificity and sonic entanglement of Hayes’ diction strikes me. The way plum draws into the palm of the first line… The way sound serves as integument … and the proliferation of y-endings… bloody, dusky ruby, husky … bulky—which then leaps into the lamenting lamb’s head and the lopped of the next line. Hayes is the maestro of strung-sonic-effects in the contemporary sonnet form.

In an interview with Lauren Russell, Hayes had the following to say about “the perfect poem”:

If you think about an animal, there’s no perfect animal. Most people think of poems like they’re machines. I’m thinking of something more organic and human that exists the way it needs to exist, more like a baby or child. How do you achieve that? I think of myself as a person who likes to be in control of everything. So how do I surprise myself? For so long I’ve been this person who’s been too in control, so how do I relinquish control? Some of it’s about line breaks, narrative. I like the poem to look a certain way in terms of line breaks, but how do I release control? Some of it is subject matter. The poet wants to be liked in the poem, but what does it mean to not always chase some kind of appeal? Discomfort, vulnerability, rawness that come up in a poem—that also has to do with perfection, the absence of perfection. That’s hard to teach, but if you make people more generous in the workshop, then you can get it. You say, “Oh, it’s not a perfect poem, but it’s pretty good; we’ll take that.” It creates generosity if you aren’t chasing a perfect object.

Refrain: It creates generosity if you aren’t chasing a perfect object.

1. 8

The game-like structure of Hayes’ essay on poetic lineage—the cards which trace influence, and challenge the simple directionality of influence we tend to read into pedagogy. I keep thinking of riffing and jazz and blues, the performances that depend on multiple variables, none of which can be easily isolated. The piece plays you; and you play the piece—and one is played by it.

1. 9

Past conditional tense is a form of privilege wielded by the present against the past.

Julian Barnes’ description—- “What mother would have wanted…” a hypothetical based on a person who lived and now doesn’t. A double-remove prone to projection.”

"The silence was so intense there might have been a sound moving around in it." (John Ashbery, Girls on the Run)

1. 10

Sunday Service

by Taylor Byas

“The Blood Still Works” stampedes through the nave

and once the organ player’s shoulders seize

with song, the spirit hits the pews in waves.

I catch the loosening necks, the mouths’ new ease

as the congregants begin to speak in tongues;

I move my lips, pretend to be saved, and next

to me, my grandma convulses—-the drums

of the band a puppet master, a hex—-

while ushers in white surround her, lock hands

to keep us in. The preacher’s sermon builds

to a screech, his sinners flitter fans

like mosquito wings, and with his eyes he guilts

me into clasping hands: I repent for things

I’ve yet to do. They jerk to tambourines.

Mike Theune on “strange voltas”— and how the “heat map” of the poem makes the volta glow. This Shakespearean sonnet enlivens the rhyme scheme with off-rhymes and slant rhymes— and I wonder if that is why Byas’ writing feels so fresh, so unexpected, so vivid. The subject is glossolalia—-or speaking in tongues. For those who haven’t observed it, the effect can be jarring: one doesn’t know whether the person is literally seizing or experiencing an ecstatic connection to the divine. Byas rides that margin between ecstasy and neurological misfiring throughout the sonnet. Lines like “his sinners flitter fans” and “with his eyes he guilts” are incredible—-as is the held breath enacted by the stanza break, the bigness of that enjambment.

1. 11

The eros of sparse sayings, the statuesque nude statue, as in Richie Hofman’s “The Romans”. I thought of Derek Jarman’s sonnet torsos, almost. But also of how the statue, like the sonnet form, craves its own ruin—or exists as erotic possibility in relation to that very ruin. As in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labor Lost, when Armado, upon discovering that he has fallen in love, says: "Assist me, some extemporal god of rhyme, for I am sure I shall turn sonnet." The extemporal god of rhyme, like the lyric poem, sits outside time; he languishes in eternity.

1. 12

Note on the extraordinary variety of form and adaption in the contemporary sonnet. Amit Majmudar's “sonzals”; Bernadette Mayer’s “deconstructed sonnets”; Molly Peacock's "exploded sonnets”’ John Berryman's "devil sonnets" (which Kevin Young has called the six-six-six); Jericho Brown's "gutted sonnets"; Joyelle McSweeney's "almost sonnets"'; Tyehimba Jess' "shattered sonnets" ; Gwendolyn Brooks' "soldier sonnets" ; Ted Berrigan's "sonnet collages"; Dorothy Chan's "triple sonnets" ; Diane Seuss’ sonnets built from the syllabics of the “American sonnet”; the sonondilla (or sardine) by Charles L. Weatherford; the salamander’s fireburst by Jose Rizal M. Reyes (and, less recently, the Pushkin sonnet by Alexsandr Pushkin).

1. 13

Bernadette M. again: I'm through with you bourgeois boys. The internal rhyme lifts this line from the page; it hovers in the air of the poem like a joke or a threat. Lines move like ruffled feathers or windblown papers, borrowing from collage:

Nowadays you guys settle for a couch

By a soporific color cable t.v. set

How the enjambment thickens "by". Buy a tv set or sit by a tv—it's all the same texture for the boys who got bought by it. Mayer brings her study of Greek and Latin prosody to the Lower East Side of New York City, where the land "of love and landlords" ties the personal to the political. Sometimes it feels as if the speaker is a female Catullus.

1. 14

The erotic cufflinks of the sonnets—the ecstasy where Donne’s holy sonnets meet Simone Weil’s asceticism. And how much tension exists in Mark Jarman’s “Unholy sonnet” series, with their focus on the reasoning mind, and their resistance to extravagance. In The Flaming Heart, Mario Praz discusses the ecstasy Bernini’s Saint Teresa:

There exists in Rome, in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, a work of art which may be taken as the epitome of the devotional spirit of the Roman Catholic countries in the seventeenth century. Radiantly smiling, an Angel hurls a golden dart against the heart of a woman saint langourously lying on a bed of clouds. [The Italian name for this work of art is "Santa Teresa in Orgasmo."] The mixture of divine and human elements in this marble group, Bernini's Saint Teresa, may well result in that "spirit of sense" of which Swinburne, who borrowed the phrase from Shakespeare, was so fond of speaking. Spirit of sense as in that love song the Church had adopted as a symbol of the soul's espousals with God: The Song of Solomon, which actually in the seventeenth century was superlatively paraphrased in the coplas of Saint John of the Cross. Inclined as it was to the pleasures of the senses, the seventeenth century could not help using, when it came to religion, the very language of profane love, transposed and sublimated: its nearest approach to God could only be a spiritualization of the senses.

Of Bernini's angel and saint, not all critics agreed with the sacralization of spiritual ecstasy. Mrs. Anna Brownwell Jameson (1794-1860), for example, declared that "all Spanish pictures of S. Teresa sin in their materialism…".

1. 15

Anthony Hecht (who has done his time with the double sonnet) takes Shakespeare’s Sonnet 151 ("Love is too young to know what conscience is") as "the bawdiest-some would say the crudest and most vulgar" of the Bard’s sonnets: "In a comic-erotic parody of the vassal's submission and fidelity to his midons, Shakespeare subordinates his soul to his body, and his body, synecdochically represented by his penis, is made subservient to the mistress to whom the poem is addressed."

Lupercalia (which also happens to be the Day of the Bear referenced in my poem, “On the Day of the Death of the Bear,” published in Copper Nickel last year)— and Hecht’s passage on it:

The Roman feast of Lupercalia, observed on the second of February, was observed as a fertility festival, celebrating both the growing of crops and the sexual vitality of humans and the other creatures. The festival coincided with the resumption of work in the fields after the rigors of winter (which, in Italy, were milder and briefer than in the northern part of the United States). But in the year 492 Pope Gelasius I abolished the Lupercalia, and substituted for it a subli- mated version known as the festa candelarum or Candlemas, dedicated to celebrating the Presentation of Christ at the Temple and the Purification of the Virgin Mary. Its ritual involved a procession of lighted candles meant to symbolize the light of the Divine Spirit.

Followers of Orpheus took the councils of dark, unlighted night as the source of the most profound wisdom. Prophecy comes to those who are willing to risk the world, or to plunge into metaphysical mania, in search of an even more disorienting ecstasy. Or this is the Orphic position’s stake in the saying. Some poets are more Orphic than others.

1. 16

David Haskell wrote what he heard from listening to trees…to green ash, cottonwood, ponderosa pine, redwood, etc. "Sounds travel around and through barriers," he said, so listening to trees "reveals stories and processes that are otherwise hidden." A botanical soundscape formed from small labs of attentive listening.

Nicole Walker: "I also love the form that wilderness imposes on the wild. That hawks must eat baby squirrels. That bark beetles decimate drought-stricken pines. That Max must go home for dinner." [Italics mine. Time as formal constraint in sonnet.]

1. 17

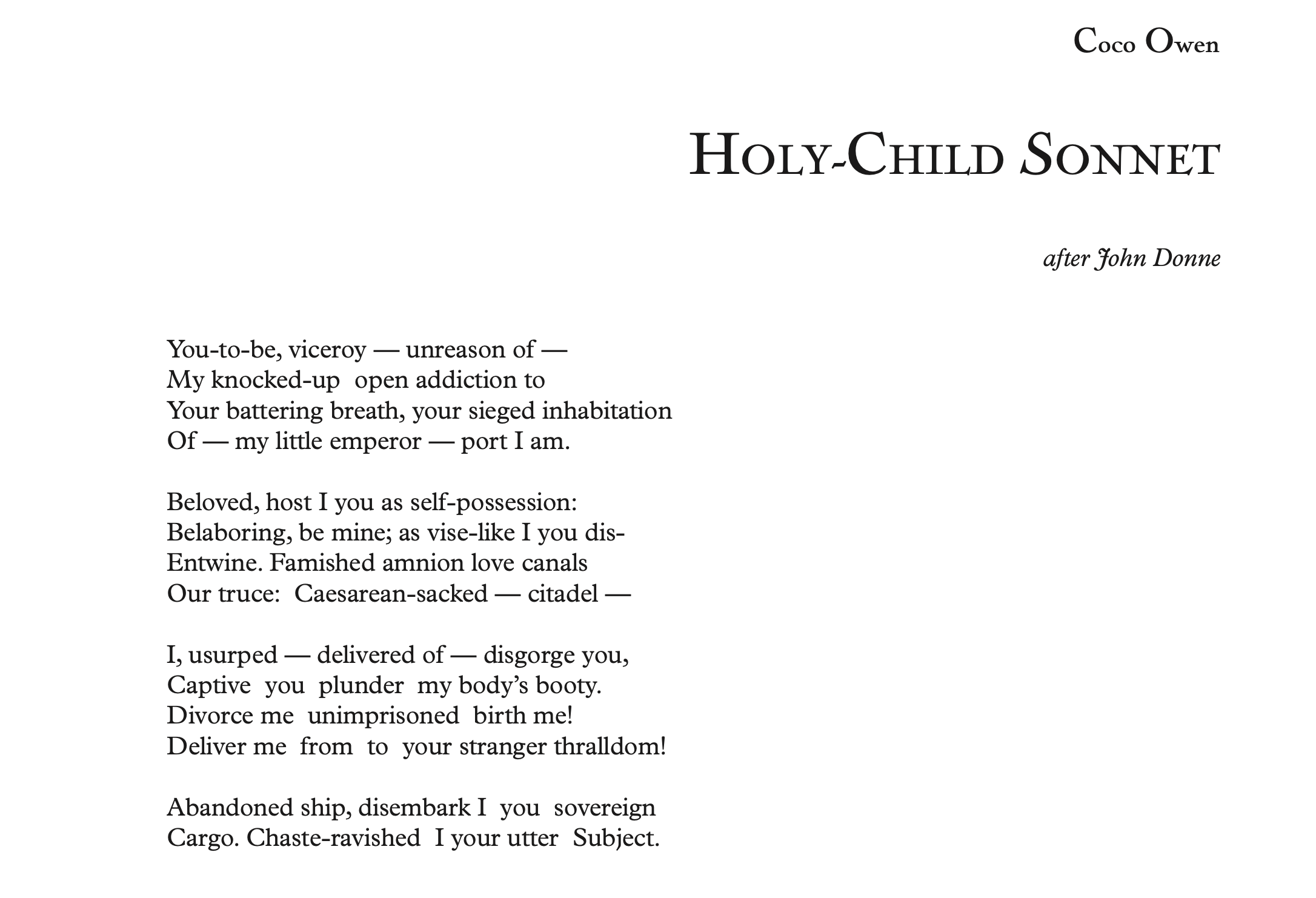

In response to John Donne’s holy sonnets, Coco Owen borrows the key words and leans into the possessive, capitalist/conqueror analogies. “Mocking little purr,” to quote Erik Satie’s tempo marking.

1. 18

A cosmology is an account or theory of the universe. The word comes from French cosmologie or modern Latin cosmologia, from Greek kosmos ‘order or world’ + -logia ‘discourse’. Cosmology is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's Glossographia. Cosmic discourse!

1. 19

"Beneath these stars is a universe of sliding monsters,” wrote Herman Melville.

Slippage is central to cosmology—and to the words selected as stars in one’s sonnet. Always the question of how to constellate them.

1. 20

Not enough time to talk about curtal sonnets or bring in Gerald Manley Hopkins. But I can squeeze in Rimbaud’s monosyllabic sonnet. On the other hand, there is sonnet energy in Johannes Göransson’s “Sugar Theses”— there are strange juxtapositions which could be culled from his words as titles or prompts:

When I’m writing about shoplifting, I’m writing about the divine. When I write novels about sugar and movies, I’m writing about war. I don’t have the proper distance toward art. I don’t believe in minimalism. I’m prone to outburst and invasions. I live in an exocity and I can taste the poisons. I pick playgrounds for my children based on the contamination levels. I pick my children up and stare at them as if they were snakes. My children are snakes. At least in the paintings of the pre-raphealites.

Fourteen lines turns into an addiction. Like a toy you want to ride everywhere just to see how it feels over different terrains.

1. 21

Variations: Clark Coolidge’s Bond Sonnets; “White, White Collars” by Denis Johnson; fraction sonnets like Elizabeth Willis’ “63 ½”; Jeffrey Thomson’s “Blink”, an enumerated, list-like sonnet: Thomas Carper’s “Catching Fireflies,” a sonnet strung from one long sentence; “Nicole Steinberg Brett’s Getting Lucky; a sonnet in a letter from John Keats. The buried-in-a-letter sonnet deserves recognition, I think, as an epistolary sonnet, even if it evades itself by wearing feathers.

1. 22

I keep coming back to Terrance Hayes, particularly when trying to decide whether to push towards use of contranyms and homonyms in sonnet prompts. Contranyms are words with opposite, or nearly opposite, meanings. An example is sanction, which means “to authorize, approve, or allow” and “to penalize, discipline”.

The magic of this in “New York Poem”—-and how Hayes continuously draws in the blue note, the jazz brush, the disco, the music in counterpoint against the “sci-fi bridges.” One could also read this as a declarative (“the sci-fi bridges) rather than a description (the bridges which look sci-fi).

1. 23

John Berryman in “Sonnet 13”, ending the first stanza’s rhyme (glass / brass / pass / alas):

“The spruce barkeep sports a toupee alas—”

The clipped, lexical control of Joshua Jones’ series, “Thirteen Sonnets in Transition.”

The way Marilyn Hacker slips her lesbian love inside a French word in “La Loubiane”:

Two long-haired women in the restaurant

caress each other's forearms. I avert

my eyes. I'm glad to see them there; I hurt

looking on, lonely, when I so much want

to touch your arm, your hand like that, in front

of two mémés enjoying their dessert

And the way Hacker begins an untitled sonnet with the line: “First, I want to make you come in my hand”.

1. 24

francine j. harris’ sonnet uses the wetland as an extended metaphor in an address to a lover or former lover or a lover somewhere between solid ground and open water.

Wetland

by francine j. harris

The sea is so far from us now. Partly I think because we

are not softspoken desire. There are rude thoroughfares

and abandoned mines that brag. They gather and pile

with ruin and vacancy. It's an accrual that is in me, it seems.

At best, a wetland. Beautiful and useless in the face of flood.

So that when we walk the perimeter, we can see the ground

starve and crack. But then fear of sinkhole is so important.

Truthfully, I am not enough to steer clear of. To fall in love again,

dear, reforested bund, is a matter of self-preservation. In your expert

opinion, will you tell me how to know you if I am forever meant

to leave you undisturbed. This will not save us, I'm afraid. A brownstone

for hummingbirds is shortsighted too, like picking out honeybees

from the dog's mouth. Then blowing on her tiny hairs like a breeze.

Love, we can wish it were so; it does not make us fit to survive.

A wetland is defined as “a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently or seasonally.” In wetlands, “flooding results in oxygen-free processes prevailing, especially in the soils.” The relationship between underground air, aeration, and the threat of sinkholes is also at play in the poem. Reforesting a wetland won’t change it, the speaker says, drawing on the ecology of the land form.

One portmanteau word—-softspoken, as if to score the composition. An archaic noun—thoroughfares— alters the texture, or expands the tone of the poem. The turn happens midway, with Truthfully, I am not enough to steer clear of. Ending the sentence with this “of” has the counterpoint motion of opening it; the internal rhyme between steer and clear pulls the reader close just as the speaker is turning, rephrasing, making her argument. Love, we can wish it were so; it does not make us fit to survive. And how carefully this final line looks the lover in the eye and says—love, yes, I grant love, but the act of wishing doesn’t make the wish capable of surviving. The wetland insinuates love cannot grow in the speaker, or between the two persons, but it harris doesn’t insist on a settled analogy (it could be the speaker or love, itself), and this element aerates the poem, somehow. The unsettledness, like the scent of sulfur near a wetland, contrasts with the physicality of eco-geology.

1. 25

Voice in contemporary sonnet: Wanda Coleman in conversation with Paul Nelson on her sonnets, 2008. The rue of Craig Morgan Teicher’s “New Jersey”. The I’ll-take-it-and-raise-you-a-triple of Dorothy Chan’s “triple sonnet for oversexed and overripe and overeager” which makes a trinity of the oversexed, overripe, and overeager—-and no question mark at the end of the question because the speaker isn’t asking, she is telling— “Don’t we all want to be the best time. / I think about what it even means to be ladylike". Enjambing the line across the stanza here.

Also noting the tendency to move between voices—to gather multiple voices into poem and use rhythm and punctuation as means of distinguishing between them—per second quatrain of Cortney Lamar Charleston’s "Doppelgangbanger":

with badge and walkie-talkie, walking up on the envoys

of decency—mom and me—doing the kid some “solids”:

straighten this. Pull up that. E-NUN-CI-ATE. I peep his ploy.

Play a historian. Hone on his perfect white teeth, horrid

Charleston’s alliterative rhinestones sparkle the scene. “The envoys of decency”—an unforgettable description.

1. 26

Ted Berrigan on "Ann Arbor Elegy, for Franny Winston died September 27, 1969," a sonnet he wrote with the intention of altering the elegy to make it "a very mild poem,” in his words:

I didn't read in the newspaper that Franny Winston had died, but rather I had read that [the boxer] Rocky Marciano had died, in a plane crash in a field in Iowa.

So, reading of his death made me write a poem about her death, which was on my mind. The sonnet seemed to me a proper vehicle for this, that is, to write an elegy, and at the same time, to write a poem in which I was making the events happen in the present, even though obviously I wasn’t writing the sonnet while they were going on. And finally, there was the transference of having read something in the newspaper about someone’s death who was not the person I was writing about. Again, the sonnet form seemed to allow me to do all those things.

1. 27

Bernadette Mayer saying in 1997: “Never. I’m sorry. I wasn’t impressed by Eliot.”

Susan Sontag saying in 1977: “There’s no opposition between the archaic and the immediate.”

Jack Ridl saying in a poem: “Dogs live knowing how to live; they alone defy Kierkegaard.”

1. 28

Listening to “From the Grammar of Dreams” (1988) by Kaija Saariaho—five different soundscapes composed from Sylvia Plath’s words— while thumbing through the Pop Sonnets tumblr and thinking of “match cuts” in relation to stanzas in Namwali Serpell’s description:

"A match cut “jumps” rather than flows from shot to shot. Unlike a splice cut, which moves smoothly from one angle or moment to another in a single setting, giving us a feeling of continuity, a match cut lasts long enough for us to notice that two shots in different settings have similar shapes or movements—we make the leap to connect them, to relate two things separated by space, time, perspective. You could think of a match cut as a visual analogy or metaphor: a purposive claim that one thing is like another thing, a “perception of the similarity in the dissimilar,” as Aristotle put it. Or you could think of a match cut as a visual pun: a trifling way to play with the fact that two things echo each other. Either way, as a technique for juxtaposition, match cuts raise two questions: What’s the relationship between the things juxtaposed? And how is the juxtaposition itself justified?"

A way to think about time and tense change within sonnets—using these questions. What’s the relationship between the things juxtaposed? And how is the juxtaposition itself justified?

1. 29

Consider word & letter as forms—the concretistic distortion of a text, a multiplicity of o’s or e’s, or a pleasing visual arrangement: “the mill pond of chill doubt.” (from Bernadette Mayer’s list of poetry exercises)

Among things found on twitter today: Hölderlin, Ovid's Return to Rome. Metrical Scheme from poem draft. Words noted in left margin:

Climate

Homeland

Scythians

Rome

Tiber Peoples

Heroes

Gods

1. 30

Joyelle McSweeney’s “hyperdiction”— the super-charged, excessive words that fill the interior mindscape brought forward to populate the poem. As if our multiple lexicons could sit together in a room and represent themselves in the overlapping, dissonant dictions.