THE CONDITIONS OF OUR SCREENING

Earlier this summer, while visiting my dad and stepmother, I found myself in a room with three adult men who had never seen Moonstruck (1987). These three—my father, my partner, and my son—have each, at different times and in different locations, described themselves as thoughtful. Suddenly, I wondered what they might think of it. Worse, I wondered what would happen if we thought about it together.

John Patrick Shanley, an Irish-American playwright, wrote the screenplay used by Norman Jewison, a Canadian filmmaker, in the making of the this Italian-Amerian romantic comedy. It was one of my mother's favorite movies, so maybe a ghost nudged me to host a family viewing that included the daughters, the stepmother, the son, the father, the partner, and the valiant king of Dada, my dog Radu. Set in New York City, the film follows the developing courtship between Loretta Castorini (played by Cher) and Johnny Cammareri (played by Danny Aiello). Family conflict and past betrayal becomes a centerpiece to the love triangle between the Cammareri brothers, Johnny and Donny, and Loretta Castorini. That’s the skeleton.

SCENE: JOHNNY ASKS LORETTA TO MARRY HIM AT THE RESTAURANT

Loretta is a widow whose husband died after being hit by a bus while crossing the street. She attributes this horrible accident to pairing: “We had bad luck,” she says, and repeats this phrase several times in the film. Due to her husband’s death, Loretta believes that this bad luck comes from having expected or desired too much. She works as accountant for the family business, dutifully managing and balancing the numbers, living obediently within a very rigid framework she has created to keep herself safe from more “bad luck.” Here’s the scene:

In the opening marriage proposal, Loretta (played by Cher) shares a romantic dinner with her boyfriend, Johnny Cammareri . He asks her to marry him while sitting at the table in the restaurant–but she refuses to consider due to her fear of bad luck. Affectionately, Loretta gives certain conditions for the way in which he asks the question—and all of these conditions are related to her belief that her first husband died because these conditions were not met. So, already, there is a level of 'improvement' involved, and a sort of control that she needs to exert over the situation.

Loretta's conditions are simple:

1. Johnny has to kneel to ask her

2. Johnny has to give her a ring

The first condition is met when Johnny kneels awkwardly and everyone pauses to look.

The second condition is met when Loretta suggests that he could give her the ring he is wearing (a class ring, perhaps). And so he does.

“We’re talking about women who ask men to marry them,” my father quips. “Women who propose marriage.”

I concede that marriage seems like a ridiculous thing to propose, if one stops to consider it.

“Marriage proposes a thing that can’t be communicated in the proposal,” I tell my father.

SCENE: JOHNNY’S REQUEST

After receiving a phone call that his mother, the family matriarch, is dying, Johnny books a flight to Italy to be at her deathbed. Loretta drives him to the airport and this is when he makes his own request—a condition of sorts, an expression of what Johnny needs in order for their marriage to be blessed. He makes her promise to invite his estranged brother Donny (played by the extraordinary Nicolas Cage) to their wedding. The brothers haven’t spoken in five years. Donny lost his hand in a freak accident in the bakery, which then led him to losing his fiancee: he blames the accident and the loss of his potential happiness on Johnny.

Again, the ghost of ‘bad luck’ frames Loretta’s response to this condition.

SCENE: AS LORETTA WATCHES DONNY’S PLANE TAKE OFF, A STRANGER INTRODUCES BAD BLOOD AND CURSES.

This conversation is interesting because it builds on the curse and bad luck theme. Conversations are opportunities for humans to think through the meaning they ascribe to events.

Elderly lady: You have someone on that plane?

Loretta: Yeah, my fiancé.

Elderly lady: [angry] I put a curse on that plane. My sister is on that plane. I put a curse on that plane that it's gonna explode, burn on fire and fall into the sea. Fifty years ago, she stole a man from me. S'aprese il mio uomo! Today she tells me that she never loved him, that she took him to be strong on me. Now she's going back to Sicily. Ritorna in Sicilia! I cursed her that the green Atlantic water should swallow her up!

Loretta: I don't believe in curses.

Elderly lady: [shrugging] Eh, neither do I.

“This is something Romanians and Italians share,” my father notes. “Curses are a way of accomplishing things.”

SCENE: WHEN LORETTA TELLS HER FATHER SHE IS ENGAGED, HER FATHER REMINDS HER THAT SHE HAS BAD LUCK.

“Isn’t Loretta’s mother articulating the condition for a happy here?” I address my question to the teens, who are valiantly ignoring me and thus increasing my respect for them while also ensuring that Loretta, by dint of fate or circumstance, will not take her mother’s advice seriously.

SCENE: LORETTA GOES TO THE CAMMARERI FAMILY BAKER TO INVITE DONNY TO THE WEDDING

Dutifully, she is fulfilling the promise she made to her fiancee while also meeting the conditions established for a safe marriage.

The meeting presents us with Donny, a character that lives in his grudges and deifies his resentment. The world is to blame for the tragedy Donny sees in his life.

In this first meeting near the blazing ovens, with fury and passion emanating from Donny, Loretta’s tries to keep the peace. We aren’t sure what she is thinking when faced with this resentful, angry man who takes Johnny’s forthcoming marriage personally.

[The discussion with my family centers on whether ‘contempt’ is an appropriate word to describe what Ronny expresses.]

Donny: I ain't no freakin' monument to justice! I lost my hand! I lost my bride! Johnny has his hand! Johnny has his bride! You want me to take my heartache, put it away, and forget?

. . . . Chrissy, over on the wall, bring me the big knife. I want to cut my throat.

Chrissy: [in an aside to Loretta] This is the most tormented man I have ever known. I'm in love with this man, but he doesn't know that, 'cause I never told him, 'cause he could never love anybody since he lost his hand and his girl.

Donny: I looked the wrong way and I lost my hand. He could make you look the wrong way and you could lose your whole head!

“Both are haunted by the failures of love past, but for different reasons,” my father concedes.

We are thinking about the part of the exchange where Donny yells at Loretta, implicating her an expectation that he forget—-“You want me take my heartache, put it away, and forget?!” Loretta doesn’t respond.

SCENE: LORETTA FOLLOWS DONNY UPSTAIRS TO HIS APARTMENT AND TRIES TO CONVINCE HIM TO COME TO HER WEDDING

In her mind, Loretta is still trying to fulfill a promise she made to her fiancee, a promise that involves bringing his family together to bless their union. She needs everything to proceed by the book with this wedding. She needs her family behind her. Their conversation take places in Johnny’s kitchen.

The camera gives us a couple in a kitchen with a significant amount of white space surrounding them. Donny blames his brother for how his fiancee left him after he lost his hand. In an effort to relate to him, Loretta shares her bad luck story.

Her husband wanted a baby and she deferred it.

When he died, she had nothing. We had bad luck.

I want to break it down a bit here.

“How did I know that man was the gift I couldn’t keep, my one chance at happiness?” Loretta asks rhetorically. She is wearing an apron and cooking a meal: the traditional gender roles are framed, and the speakers develop accordingly. From within this matronly costume, Loretta delivers her Wolf Monologue that offers an alternative (and rather fantastic, myth-inflected) theory as to why Johnny lost his hand.

Loretta: That woman didn't leave you, OK. You can't see what you are, and I see everything... You are a wolf!... That woman was a trap for you. She caught you and you couldn't get away. So you, you chewed off your own foot. That was the price you had to pay for your freedom... And now, now you're afraid because you know the big part of you is a wolf that has the courage to bite off its own hand to save itself from the trap of the wrong love. That's why there's been no woman since that wrong woman. OK? You're scared to death of what the wolf would do if you try and make that mistake again!

She is presenting Donny with an alternate imaginary—-an imaginary culled from the long-married couple that owns the bodega. And something shifts between Loretta and Donny in this moment when she tells him a story about his life, a story that fashions him as a wild creature rather than a helpless victim of circumstance.

Donny: What are you doing? [looks away to the left]

Loretta: I’m telling you your life.

Donny: Stop it. [looks back at her, unbarbed]

Loretta: No!

Donny: Why are you marrying Johnny? He’s a bore!

Loretta: [sighing, shaking her head, looking upwards] Because… because I have no luck.

Donny: A bride without a head!

Loretta: A wolf without a foot!

“Oh,” Loretta sighs, “I don’t care! I don’t care anymore!” She lets Donny take her to bed. It’s not clear yet what she is giving up on.

Loretta: What are you doing?

[Donny lifts Loretta into his arms and begins walking across the room with her]

Donny: Son of a bitch!

Loretta: Where are you taking me?

Donny: To the bed.

Loretta: Oh, God. I don't care. I don't care. Take me to the bed.

As the two climb out of bed the next morning, surrounded by the mess of their clothing, Loretta tells Donny to “snap out of it” as he starts professing his love for her.

At this point, P determines that this movie is "all about family" rather than romantic love. I disagree, but I’m intrigued that he should pick this particular scene as an expression of all-about-family.

For me, Moonstruck is all about the conditions for relating, or relationality, and how the idea of betrayal is configured interpersonally. The film begins with an engagement scene and it ends with an engagement scene. Troths are pledged. Betrothals occur. It could be classed as a double-engagement plot.

The altered topography of positions and gestures and proximity in the final scene stands in contrast to the opening scene—and the film seems to say something about marriage in that juxtaposition. P responds with a shrug, unconvinced.

SCENE: MONTAGE OF LORETTA PREPARING TO GO TO THE OPERA WITH DONNY

I hate it. Let me swerve along this horizontal axis into an aside. My experience with Sex and the City is limited to the five episodes I watched with a college friend. As my friend told it, Sex and the City taught about ‘the importance of having your own place’ and ‘girls just wanna fun’; it also made her feel ‘validated’ to see Carrie had a dildo. For me, the intellectual take-away was less impressive. After doubling the number of joints smoked before episodes 2 and 3, and keeping my bong loaded between my knees for the duration of the 4th and 5th episodes, I ran out of weed. This is what forced me to accept that I could not possibly continue watching that show with my friend. There was no way I could smoke the amount of weed I required in order to properly appreciate Sex and the City. For all I knew, that amount could be infinite, since I had yet to enjoy a single episode, despite doing my best and going so far as to feed my entire dime bag of KB to the bong in the name of girl talk, sexual lib, and empowerment feminism. The truth is that I had wasted a precious thing, namely, the KB, in the hopes of overcoming my resistance to kitten heels and coyeurism.

“I learned that my dealer isn’t going to New Orleans for another two weeks,” I said to my friend when she asked what I thought about Carrie. I also avoided her next question. One could say I learned that avoiding questions is preferable to answering them when high-femme is on the table. If I mention this at all, it is because there is a part in Moonstruck that reminds me of what would later be groomed into neoliberal femininity and I left the room while my son, father, and partner watched it because I did not have enough or truly any weed.

What am I avoiding?

The extended montage of fashion fantasies and beauty parlors shows Loretta undergoing a vigorous regime of mani-pedi, tip to toe body hoovering and make-overing. Every girl dreams of the perfect dress for her wedding: that’s the conventional assumption being rubbed here. Framing shots and images make much of the scenes in which Loretta splurges on the dress dream, and one could of course speculate that the director is setting up an alternate pre-wedding fantasy. When she wears this dress, Loretta will become a new person. So we are supposed to feel happy as she splurges, elated by the new heels appearing like Cinderella dreams, charmed by the culmination in a disgusting fireside scene with romantic shading and gauzed edges.

She ‘treats herself,’ so to speak, and this could be read as a sign that she is turning over a new leaf. But the problem with turning over a new leaf is that it remains a cliche, a way of gesturing towards a vague thing that means nothing. Since I am being unfair in my description, I will quote from a blog post written by a woman who loves this montage:

And then, it happens. A perfect scene, as far as movies go: Loretta’s mini-makeover-montage as she prepares for a life-changing evening at the opera with Ronny. She spends the entire day caring for herself — paying attention to her desires, to her heart, to herself. It’s a beautiful sequence of scenes, in which we see Loretta alone, deciding to take her life back.

Here’s what happens:

She first heads to the Cinderella salon (hello, metatextuality!) and has the gals dye her frazzled grey to a stunning raven black. She leaves with a full blow-out, her curls voluminous and sexy. The expression on her face is like she has suddenly remembered some long-dormant version of herself and decided to wake back up. Men whistle at her, and despite herself, she likes it.

On her way home, she passes a beautiful red dress in a shop window. She ducks inside, comes back out with bags. She bumps into two nuns. She can barely look at them — their presence compounds her guilt about spending the night with Ronny, but also does not make her feel bad enough to cancel their date.

When she finally arrives back to the multi-generational home she shares with her grandfather and parents, she is blissfully alone. The home is quiet and dark. This is a rare treat. Rather than waste it, spiraling in anxiety, or attempting to cancel, or trying on a million outfits…Loretta indulges herself.

She calmly pours a glass of red wine. Her freshly manicured nails, painted in a fiery red, click on the glass. She puts on a record. She lights a roaring fire.

All the weed in the world is not enough.

SCENE: DONNY AND LORETTA GO THE OPERA IN ORDER TO MEET RONNY’S REQUEST FOR THIS ONE SPECIAL THING.

This, too, is a condition: it is Donny’s condition for the end of their affair. He will go to the wedding and be cool about things if Loretta goes to the opera with him. He wants her to go to La Bohème with him. It is his favorite opera: he knows each twist and turn, each bridge and aria. For Loretta, opera is exciting but strange: it isn’t central to her life the way it is for Donny. She isn’t an opera lover.

[La Bohème inspired contemporary musicals like Rent and Moulin Rouge: all three give us the tragedy of lovers who are doomed by their love, bound by their economic and social conditions, where idealism and a romantic view of art provides an escape from those conditions. Beauty is bound to truth on this view, and beauty is of course complicated by it.]

My father is moved by how Loretta weeps during the opera, and how Donny reaches for her hand and kisses it. “He’s a gentleman,” my father says.

“It’s a tragedy,” the son announces, when Loretta reviews La Bohème, saying: “That was so awful. Beautiful. Sad. She died!”

The words Loretta uses invoke the tropes of Romanticism: Beautiful. Sad. Awful. All co-existing. Ronny knows these tropes well (“She had TB,” he replies with a melancholy shrug); Loretta is discovering them (“I know! She was coughin’ her brains out!” she cries.) Their conceptions of love are being negotiated in their response to the opera, which is precisely what Ronny intended.

SCENE: RONNY WALKS LORETTA HOME AFTER THE OPERA

Of course the moon is full above them. And “Cosmo’s moon” could be read, at this point, as the moon of betrayal.

Loretta tells Ronny her nature is drawn to him, but she doesn’t have to follow it: “A person can see where they’ve messed up in their life, and they can change the way they do things. And they can even change their luck.”

“The currency of love is the kiss, and I don’t see that happening at this point,” my father says.

How do we read a kiss?

In ancient Greece and Rome, the kiss served as gesture of reverent salutation designating affection between friends. It established proximities amid the developing public space.

Inch forward into Christian iconography and one finds the kiss shifting into an indicator of penitence and worship. The pious woman repented by kissing Jesus' feet. “Salute one another with a holy kiss," Paul grumbled in Romans, thus turning the kiss into a sign of membership in the nascent Christian brotherhood.

There is this Catholic kiss, this perfect kiss, hovering in the background of Moonstruck. A salvific kiss.

“I don’t believe in salvific kisses,” I admit.

“Judas betrayed Jesus with one,” a teen adds.

Loretta: You ruined my life!

Ronny: No, I didn't.

Loretta: Oh, yes, you did! Oh, yes, you did! Y'know, you got them bad eyes, like a gypsy, and I don't know why I didn't see it yesterday. Bad luck! That's what it is. Is that all I'm ever gonna have? I should have taken a rock and killed myself years ago!

When playing billiards, a kiss is a very slight touch of one moving ball to another. The ball kissed it and kept moving. But the kiss stops it in its tracks.

No one pays attention to my billiard analogy.

Ronny: Everything seems like nothing to me now, 'cause I want you in my bed. I don't care if I burn in hell. I don't care if you burn in hell. The past and the future is a joke to me now. I see that they're nothing. I see they ain't here. The only thing that's here is you - and me.

What would it mean to restore the scene of this double-engagement comedy?

SCENE: ROSE STROLLS THROUGH THE CITY WITH PERRY, WHO COULD BECOME HER LOVER

Perry: We could go to my apartment. You could see how the other half lives.

Rose: I'm too old for you.

Perry: I'm too old for me; that's my predicament.

Rose: You're a little boy and you like to be bad.

Rose: No, I think the house is empty. I can't invite you in because I'm married. Because I know who I am.

Father and daughter confront each other about their infidelities. “What am I going to tell him?” Loretta asks.

“Tell him the truth,” Cosmo replies. “They find out anyway.”

SCENE: EVERYONE GATHERS IN ROSE’S KITCHEN FOR FINAL RECKONING

But in the final scene, the Kitchen Reckoning, it is daylight. The entire family is gathered in the room. There is no romantic candlelit dinner. Cosmo's moon has no place in the kitchen.

Rose: Have I been a good wife?

Cosmo: Yeah.

Rose: I want you to stop seeing her.

[Cosmo rises, slams the table once, and sits down again]

Cosmo: Okay.

Rose: [pauses] And go to confession.

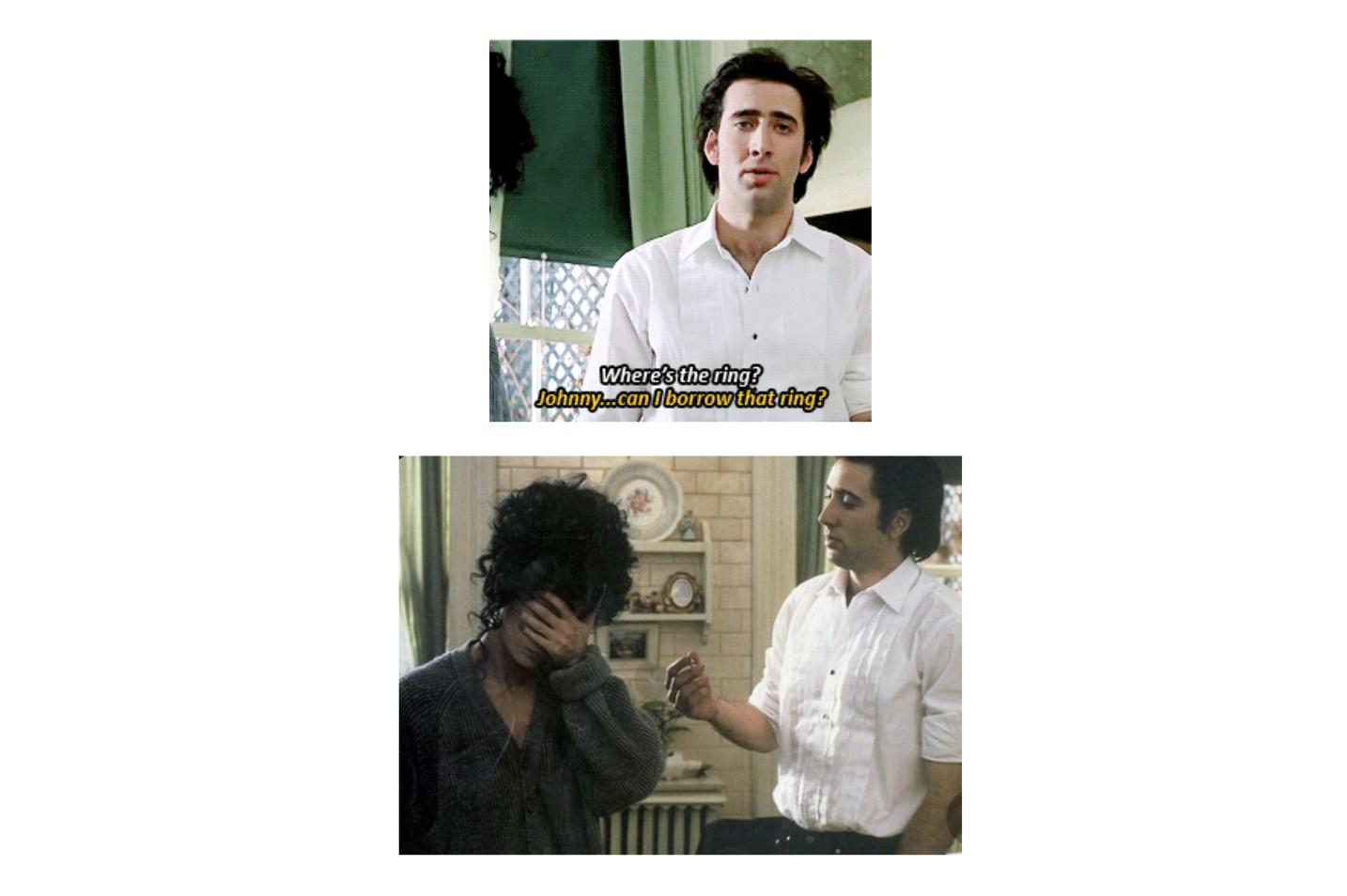

When Johnny announces that he has to end the engagement because his mother needs him, Loretta returns his ring.

Then, when Donny asks her to marry him, the two are standing, the window behind them, and she says yes, absolutely - without asking him to kneel. Spontaneously, Donny turns to his brother, the dumped ex-fiance, who is still kneeling, and asks him to give him the ring. So the ring goes back on Loretta's finger - the same ring used for one engagement - but no bad luck is mentioned.

Bad luck only seems to be a concern when the expectation of marriage includes security and happiness. If love is ruin, as Donny says, a curse is nothing. A curse is petty currency, given the grand scheme of things.

When Loretta agrees to marry Ronny, Rose turns to her and asks: “Do you love him Loretta?”

Loretta replies, "Ma, I love him awful.”

Awful is a strange modifier for love. We read over this because we assume that Loretta is using a cliche, namely, I love him an awful lot, which means—-but that’s not how the phrase is intonated when Cher performs it.

Rose: I just want you to know no matter what you do, you're gonna die, just like everybody else.

Cosmo: Thank you, Rose.

"It's not a comedy," P. insists. "It's a romantic drama."

“It’s a tragedy,” the son repeats.

“It’s life,” my father adds, pouring himself another glass of schnapps.