Blason means “coat-of-arms” or “shield” in French. From French heraldry, blason translates as “the codified description of a coat of arms”

As a poetic genre or technique, blason (or blazon) comes to us from 16th century French poet Clement Marot, who penned a poem celebrating a particular woman by listing parts of her body which he then compared to incredible things. Although Marot’s blason anatomique set the standard for blazons to come, its roots come from medieval heraldry, with its iconic representations of families and their attributes. Heraldic devices represented the entire family, or, in some cases, knightly qualities (e.g., the pentangle in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight).

In the blazon, the physical traits of a female subject are catalogued, often in sonnet, sonnet sequence, or love lyric, and described by individual parts rather than the body as a whole, so parts of the body compared to gems, jewels, celestial bodies, sunrise, and various aesthetic glories. Gilded by ornate, eroticized, the "real" woman disappears, and her image is reconstructed according to the male poet's point of view, resulting in the recreation of an idealized woman who thus becomes his possession.

It is the poem that gives the man the woman of his dreams. And should it be otherwise? Shouldn’t the man possess the woman he has invented for his poem? Ethical aesthetics aside, one sees the blazon move into English through the influence of Petrarch, whose sonnet form thrived during the Elizabethan literary period. Edmund Spenser, for example, uses blason in his poem, “Epithalamion,” where

Her goodly eyes like sapphires shining bright,

Her forehead ivory white …

The simile compares his subject’s eyes to shiny jewels; the describes her perfect forehead, etc. Spenser also used this technique in “Sonnet 64” from Amoretti, comparing each feature of the beloved woman to a flower. A whole garden in a woman’s body! A stunning tablecloth!

Sir Philip Sidney’s “Sonnet 91”, a Petrarchan sonnet from Astrophil and Stella, parodies the blazon by questioning singularity. Here, we find the speaker, Astrophil, missing his love, Stella, and warning her not be jealous if he sees or interacts with other beautiful women, since all he can see when he looks at them is her:

They please, I do confess; they please mine eyes,

But why? Because of you they models be,

Models such be wood globes of glist’ring skies.

Dear, therefore be not jealous over me,

If you hear that they seem my heart to move.

Not them, oh no, but you in them I love.

It’s a self-soothing parody of what the blazon idealizes, namely, a single beloved woman — though perhaps this isn’t clear to Astrophil, who uses pieces and body parts drawn from other women to keep himself from getting despondent with longing. All women lead back to you, Astrophil suggests.

Sidney published this sonnet in the 1580s, more than a century years after Martin Behaim, a German cartographer, made the oldest existing globe existing in 1450. In a line from the sonnet, Sydney compares the beauty of the women he sees to wooden globes, with painted constellations and planets — which, again, points back to the visual.

*

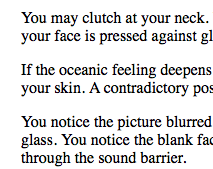

The male speaker's voice carried the 16th century "blason" poetic form, with its erotic declensions of female body parts — but one man’s sacred cherries may be another’s man scarlet marbles. Another convention: in its earliest forms, the blazon leaned on syllabics at the level of the line. The octosyllabic or decasyllabic verse often culminated in an epigraphic conclusion.

Thomas Campion’s use of blason is infamous — and visible in the illustration at the top.

“Her eyes like angels” would return in 1990’s pop and various porcelain motifs stored in curio-cabinets.

The contreblazon inverts the convention by describing “wrong” parts of the female body (as in the visual form at the top), and the antiblazon relies on negations and negatives to describe the female, as William Shakespeare did, insisting his mistress’ eyes were “nothing like the sun.”

In antiblazon, an individual woman is fragmented, but this division is done to describe reality, not to create (or sustain) an idealized portrait. Supposedly.

So what would happen if the female voice set her sights on the male body in blazon? Isn’t it subversively playful for a woman to narrate a blason, to bring it closer to a pastiche, to lay a tooth inside the heart of the erotic pulse driving the male gaze?

For a contemporary example in which the female speaker catalogues the male lover, read Camille Guthrie’s “My Boyfriend”. I suspect Jean Valentine uses a fair amount of blazon in her love poems, particularly “First Love” (more on this in another post, if time permits).

*

Cards on the table: what drew me to the blazon this week was a mystery which may be a misunderstanding, certainly a fascination in Louise Labe’s Love Sonnets and Elegies, edited and translated by Richard Sieburth for NYRB Imprints.

Controversies about Labe’s identity and authorship abound, but I incline towards the assessment of Samuel Beckett’s Dream of Fair to middling Women, whose character, The Polar Bear, declares Labe: “A great poet, perhaps one of the greatest of all time.”

The pleasure of paradox formed an aesthetic, a flourishing field of paradoxical encomiums inspired by Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly. The Venetian poet, Ortensio Lando, published a book of paradossi in Lyon around the same time as Labé. Sieburth defines the umbrella term, adoxography, as “an ancient rhetorical practice based on a wry, semi-satirical laudation of persons, objects, or states that are in themselves unworthy of praise—such as poverty, drunknenness, ugliness, blindness, stupidity, folly, or, as the case may be, woman.”

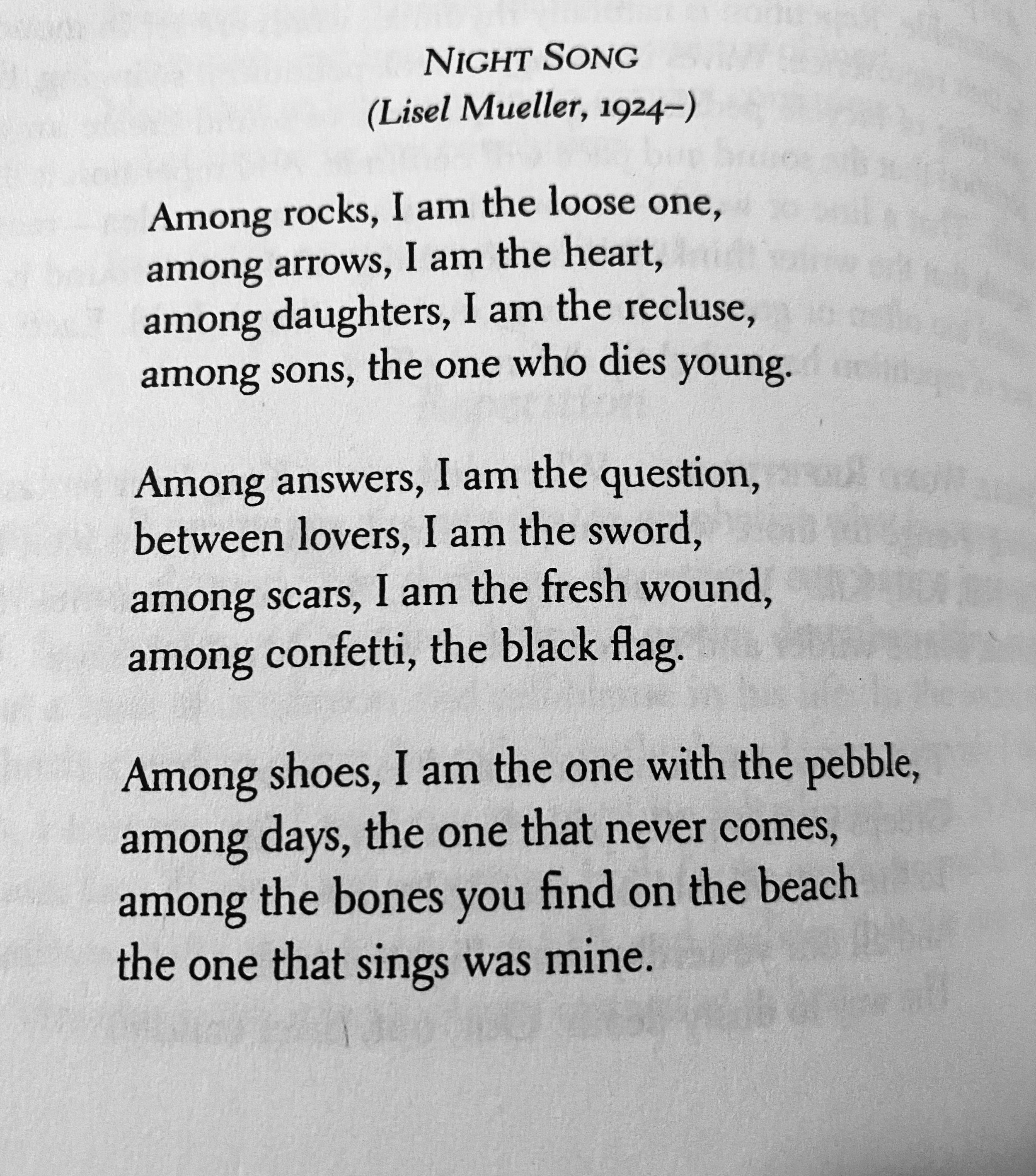

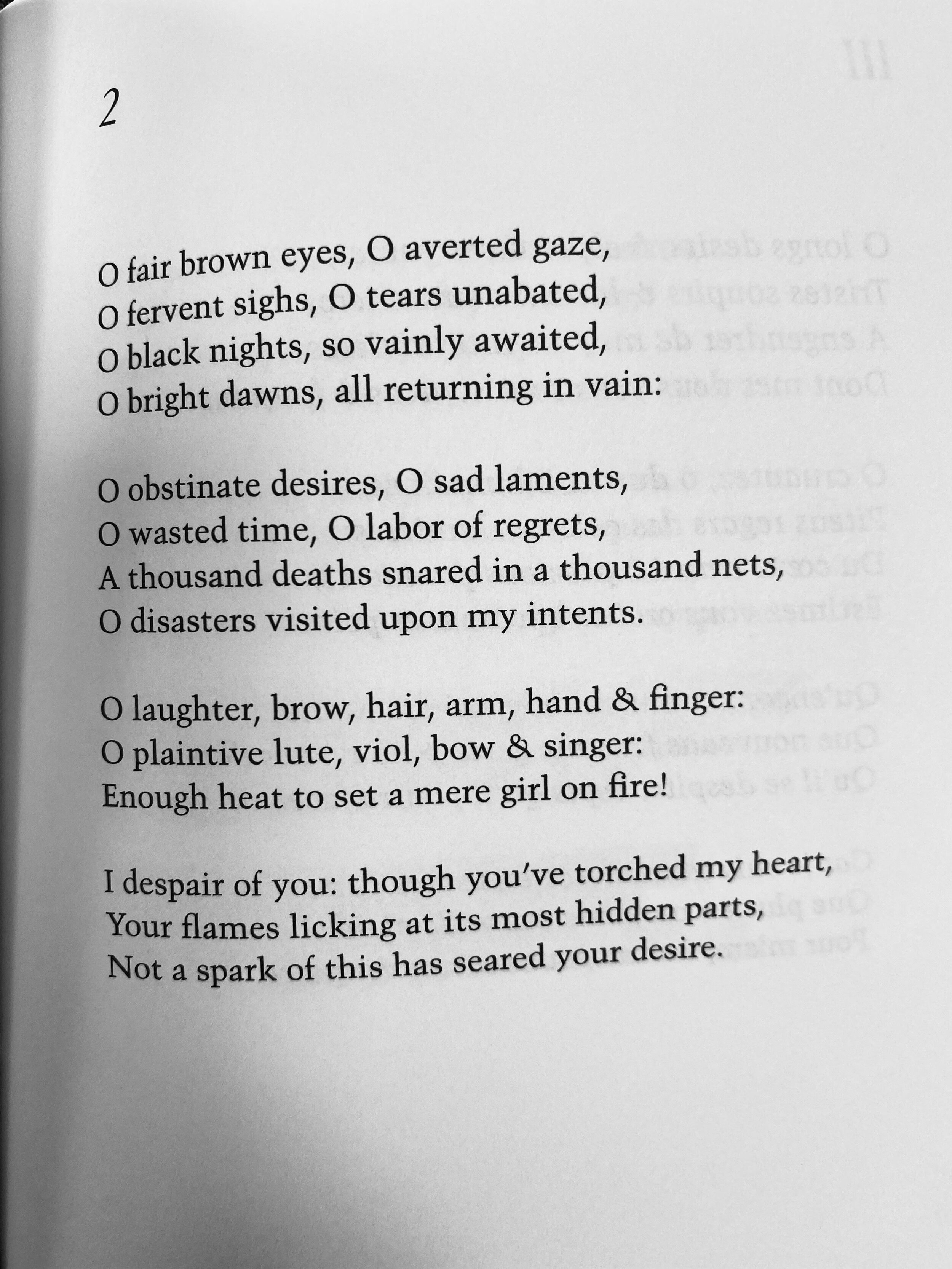

Louise Labe's "Sonnet II" incorporates the blazon, which translator Richard Sieburth takes to be "queered" by the fact that the first two quatrains, the octave, are identical to those of a sonnet published two years later by Olivier de Magny in his own book of poems, Soupirs. de Magny was Labe’s former lover; they wrote together in Lyon. Francoise Rigolot suspects Labe and de Magny drafted the octave together “perhaps as a game or contesting the idiom of the Barthesian lover’s discourse of he day; then, in the sestet, the two went their separate ways.” Thus, the paratactic apostrophes could be his or hers.

These is Labe’s version of the sonnet. Now for de Magny’s, which I will pick up from the shared final line of the second quatrain:

O stuttering steps, O flames that burn too warm

O sweet errors, O thoughts of my soul

That, day and night, whirl me back and forth,

O you my eyes, no, not eyes but fountains,

O gods, O heavens, O humankind,

For the sake of God, be witness to my love.

Notice how de Magny placates all gods, all deities, moves from the minor gods to the major God, as capitalized in the last line. His poem is speaking to the sky, to the troubadour of abstraction, while Labe’s poem ends by addressing the lover, himself. Both endings reflect different levels of amatory commitment and agency: one by disclaiming emotions to the ether, the other by questioning the male’s commitment to desire and love.

Siebruth calls it “the perfect palimpsest of an androgynous poem.”

*

Another interesting connection between the language and the performance of the poems, which is to say, the formal tools and the parodic possibilities of embodiment, appears In Labé’s Sonnet XII, “Luth, compagnon de ma calamité” (“Lute, sounding board of my calamity”), where the poet-speaker describes composing the poem as a process in which she discovers the words while hunched over a lute, her tears dripping onto the instrument’s body.

Since members of the cultural elite were expected to demonstrate their vocal and instrumental skills in salon-like social events, artists like Labé may well have tried to maximize the impact of their new poems by performing them musically, not just reciting them.

The octave ends with “toning the major into a minor scale,” but major and minor scales as we know them, in the modern sense, had not been invented yet. The end-notes have Labe referencing whole tones and semitones, that practice of music ficta that required the feigning of pitches which lay outside the strict theoretical conventions of music recta. Sonnets may have been transposed into musical form for public performance, and this may have been more true for female poets than males at the time.

One must add to the list of Labe’s influences: the lyre a woman needed to play in order to be heard, the performance of convention to pacify the male poets on the scene. One must acknowledge a theme in her poems, namely, the resistance to crediting gods or invisible entities for love — an insistence on individual agency and responsibility for the heart’s hungers. One must give the poet, herself, the last word, in Sonnet 24:

No need to blame Vulcan if you’re on fire,

Nor Adonis to explain your desire:

Love alone decides when you lose your mind

![[Original photo source; words added from my notes]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5aea0d8696e76f6ac6f09e3c/1605725163958-S7MONOB04NMVV73NCE8G/Lipska.jpg)