1.

Mozart's pet starling, Jester, died in the same week as his father. Mozart created an elegant funeral asking friends to come suited and sing hymns. He recited an elegy he'd written at the graveside. "Musical Joke K, 522" is said to have been composed a week later, riddled with starling chatter, rambling disjointed sounds and pranks, a tribute to dear Jester.

2.

It is haunting to stand in the middle of a thing, but you cannot stand in the middle of this.

- Marianne Moore, “A Grave”

An elegy is a lament that sets out the circumstances and character of a particular loss. It mourns, exalts, and seeks to evoke the deceased.

Etymologically, the word ἐλεγεία, was derived from various Greek words: the noun ἔλεος ('pity'), the expression of lament ἒ ἒ λέγειν ('to say ah ah') or the similar εὖ λέγειν ('to speak well'), reflecting a key feature of θρῆνος, the praise of the deceased.

Mark Strand and Eavan Boland describe the elegy’s structure as wrought from “slowly evolving customs and decorums” rooted in social expectation. This root exists because, for many years, the elegy was a public expression of emotion rather than a private one. This public address shaped each elegy according to the customs of death and mourning in its society of origin. For Strand and Boland’s, the best elegies reflect this struggle “between custom and decorum on the one hand, and private feeling on the other.”

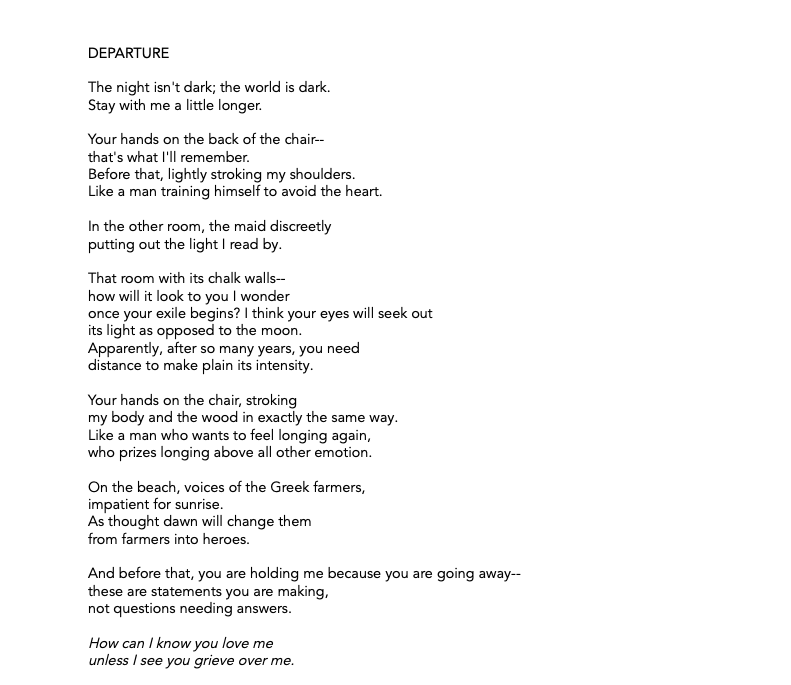

By Louise Glück’. From Meadowlands.

3.

I love the way Louise Glück ends this poem. It’s from her poetry collection, Meadowlands, which mourns the end of a marriage by retelling the myth of Odysseus, by occupying it’s corpus. The poems vary between speakers, including Odysseus, Penelope, and Telemachus. “Departure”— the poem referenced above—seems to be from Penelope's perspective.

The Latin love elegy was marked out by Ovid in his Amores, which brings an elegaic couplet first used by Greeks in funeral orations. After being banished to Tomis, Ovid announced he would no longer bother with epic forms —instead, the elegy would be the vessel to describe exile, which he likened to death.

Anne Carson’s Nox is an elegy which takes the shape of an epic poem, borrowing from Cattullus. Maybe she plays with myth and elegy and mourning in The Beauty of the Husband: A Fictional Essay in 29 Tangoes as well. Here’s a poem from that marvel of a book.

4.

we proclaim the sacred languages forever spoken by all people:

I'm afraid, I'm happy, I love you, I want to eat.

Tomaz Salamun, "The Hymn of Universal Duty"

Natalie Bakapoulos takes the protest as an elegiac form, a lamentation that mourns the way the world is:

A protest is also a lament, a collective, performative wail both public and private that demands to be rightfully heard—a hope to transition into a new, better, space of justice and dignity. There’s a sense of power in lament, a mix of rage and grief, and to lament is to wildly express an emotion in a socially sanctioned way. It’s not only an expression of grief, but a mediation of it—and a license to express pain in a way that might otherwise be considered disruptive. Or, in some ways, to purposely disrupt as witness. The words for protest and witness in Greek are linked, after all.

5.

In his essay, "Surviving on Small Joys," (from The Cant' Kill Us Until They Kill Us), Hanif Abdurraqib approaches elegy as a space in which absence can be addressed, made visible:

For poets, the elegy is a type of currency. So many of us are, especially now, speaking to the dead, or asking the dead to speak again, or apologizing to the dead for the lives we still have. Particularly for poets of color, queer and trans poets, the contemporary elegy often exists as half-memorial, half-statement of existence. Something that says You have taken so much from us, but we are still here.

I think of how poetry has stepped into that space with anthologies like Pulse/Pulso: In Remembrance of Orlando, edited by Roy Guzman and Miguel M. Morales, a memorial for the June 12, 2016 shooting at Pulse nightclub which killed 49 and wounded 53 LGBTQA persons. It is significant that those persons were doing nothing except dancing, loving, flirting, laughing, celebrating life. To be indicted and executed for one's joy is what America offers its openly-queer residents. It is almost as if they were guilty of refusing silence.

6.

Silence is a form of burial; it is a graveside manner which burns the absence into a time as soundlessness.

In “On Future And Working Through What Hurts", Abdurraqib approaches the summer after his mother's death more intimately:

The real grief is silence in a place where there was noise. Silence is the hard thing to block out, because it hovers, immovable, over whatever it occupies. Noise can be drowned out with more noise, but the right type of silence, even when drawing, can still inside inside of a person, unmoving.

The elegy is an opportunity to end the silence, to speak life into the space of loss, murder, destruction, theft, terror. Like Haniq, I hurt everytime a book is published and my mother is not there to feel redeemed by it. Of course part of this plays to her need, as an immigrant, to believe her daughter's worth could be measured by acceptance--but most of it is the earnesty with which she loved me and hoped the best for me, despite knowing, by heart, the worst. To quote Haniq again:

It is my mother's birthday. If she were living, she'd be celebrating 64 years today, and I am in an airport holding something in my hands that she might have been proud of, and I can't take it to her in her living hands and say, look, look at what I did which the path you made for me.

But the elegy doesn’t end silence: it only establishes a relationship with it.

7.

Shara Lessly's review of Emily Berry's collection about her mother's death treats the limits of the elegy as a form, itself, noting that Berry resists the confessional mode for a "matter-of-fact" mode that "presses language structurally, experimenting with staccato lines, caesurae, white space, prose fragments, and a lyric play written in two voices, among other more traditional poetic forms."

Bumping up against what she wants more of, namely, the poet’s mother, Lessly traces how this desire for revelation is related to the form itself, since “part of elegy’s tradition is decorum,” the alternating lament and praise forming a sort of postmortem portrait. “Elegies typically reveal some personal details about the deceased, even if those details are imagined or suggested via metaphor,” Lessly continues:

Traditional elegies, in other words, individualize their subjects. Through intimacy they relinquish distance and time.

8.

Craig Morgan Teicher's poem, "Death", combine multiple modalities into a single humming, humming, starting in suburbia, a familiar place that is not a place-ness, widening the circles, and then returning to suburbia, ending their after revealing its fragility. The poem is about his mother's early death in her sleep – and then his own fear of death, or what he wants preserved and remembered.

How quietly the shock begins,

like thunder rolling in,

so softly at first

one mistakes it for something else,

each generation learning alone,

anew, each of us privately aghast,

embarrassed, hiding as if until

it passes,

this one long night.

The reader sees light dies, which leads to the mother dying, which assumes the poet will die which assumes others are born and a suburban party dies in detail.

9.

I love CT Salazar’s poem, “If A Star, Break This Elegy Into All Its Reaching Fingers,” for its reliance on the conditional, or what must be the case. Or the enabling condition;

If a star, cosmos me laughing.

If a star, swear me light.

Revealing the stakes, or the conditions for love, feels vulnerable—it has all the dread of an efficient prenup, but that is what makes it feel so good in a poem, so risky. The stakes of the inanimate are part of the seduction involved in self—disclosure, and the risk is the vow of the confessional.

10.

In "About One Poem," Joseph Brodsky approached Tsvetaeva's "Novogodnea"; he says a poet writing an elegy about a fellow poet creates a kind of self-elegy or "self-portrait" radiating their own mortality. Also a way of putting oneself into the picture, of claiming relationship in the kinned poet cosmos, of saying I too loved you and deserve to be remembered in that. For the elegy transmits only our perceptions of the dead and not the dead themselves.

Tsvetaeva's elegy to her young protege, Nikolai Gramskii, who died from falling under a subway train in Paris, is a cycle of poems titled "Nodgrobic", or epigraph or tombstone. Gramskii died in 1934 but T. takes a series of photos of his empty study, the room he left before going to the metro, and tries to recreate his final moments. She insists on poetics as aural-- "In poetry Pasternak sees, whereas I hear".

In "Nodgrobic," it is Gramski who speaks; it is he who writes his own elegy from the absent space around his desk, and the icon above his bed, painted by his mother.

Before leaving Paris to return to the USSR in 1939, Tsvetaeva stopped by Montparnasse to purchase an actual tombstone nameplate for her husband's parents and brother who had died 30 years earlier. Sergei Efron's father died from illness in Paris. Less than a year later, his youngest son Konstantin took his own life. When his mother Elizaveta discovered this, she hung herself on the same day. Tsvetaeva pays tribute to her own tribute by taking a photo where her shadow hangs over their grave.

11.

More on Brodsky: the tone of elegy reveals the sort of relationship that existed. Joseph Brodsky's "Elegy: For Robert Lowell" reveals how formality and distance speak to the insecurity of a particular relationship. The poem is narrated from the pew of Lowell's "church-headed New England":

What is salvation, since

a tear magnifies like glass

a future perfect tense?

The sections wander through places like the airport, the Charles River banks, the lawns, where the poet imagines or remembers Lowell--but not as direct presence, the way he did with Auden--more as a writing buddy, a relationship tinged with fascination and wobbly hierarchies.

In the republic of ends

and means that counts each deed

poetry represents

the minority of the dead.

This is an elegy tinged with nostalgia and unfinished conversations more than harrowing grief. Brodsky is exploring the role of the poet, and replaying religious conversations, while probing the duty towards death:

It might feel like an old

dark place with no match

to strike, where each word

is trying a latch.

In his essays, Brodsky identified with the poet’s role in immortalizing and preserving the present. In “Strophes,” a poem addressed to his wife, Brodsky inhabits the role of immortalist explicitly:

I've done my best to immortal-

ize what I failed to keep.

You're done your best to pardon

all my blunderings.

In general, the satyr's song

echoes the rustle of wings.

Though this poem is addressed to his wife, a sort of dim apology, also a bitter grief at having failed to be faithful. Brodsky suggests that at least he made her famous and gave her a space in his poems forever. Perhaps this is the opposite of an elegy--or else, it's most vindictive form — something close to Ovid’s poems for his wife in Tristia.

An elegy for a person may be evoked by a scene or place. Brodsky's elegy, "York: In Memorium W. H. Auden", begins in the tie between the dead and Auden's old residence. We know by way of allusive description: "the butterflies of northern England".

The poet addresses the poem to Auden, speaks to Auden, quotes Auden back to himself ("I have known three great poets. Each / one a prize son of a bitch") in this conversation with a place haunted by his spirit. This constant swiveling between landscape, scene, and direct address keeps the elegy moving, gives the loss a sense of presence and motion.

Time is part of the memory: "Four years soon / since you died in an Austrian hotel". Brodsky ends the elegy with a single line stanza about the body trying to be found or caught by the poem:

thus the source of love turns into the object of love.

12.

A word is elegy to what it signifies.

- Robert Hass in “Laguinitas”

There are so many elegies in addition to the elegies I’ve referenced above— so many revisions of elegies, so many variations on lament— I can’t list them all, but I can share a few which offer interesting angles from which to address the unfathomable.

“The Kübler-Ross Joke” by Jason Schneiderman (addressed to the absent)

”After” by Patricia Hooper (addressed to the absent)

”Unfriending the Dead” by Janelle Clausen (addressed to the absent)

"The Moment When Your Name Is Pronounced" by Forrest Gander (addressed to the absent)

“A Grave” by Marianne Moore (in dialogue with memorial site)

“Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” by Thomas Gray (in dialogue with material memorial convention)

“Dedication for a Plot of Ground” by William Carlos Williams (in dialogue with material memorial convention)

“Epitaphs", for Eric” by Brian Culhane

”Stint” by Sally Ball

"There Was Earth" by Paul Celan (trans. by Michael Hamburger)

"You're Dead, America" by Danez Smith (protest elegy)

“Not An Elegy for Mike Brown” by Danez Smith (up-ending elegy)

“What This Elegy Wants” by Sara Elkamel (protest elegy)

”The Inefficiency of Burning” by Jonathan Moody

”Untitled (Drone Poem)” by G. C. Waldrep

“Adonais” by Percy Bysshe Shelley, an elegy to his friend, John Keats

"In Memoriam Paul Eluard" by Paul Celan (trans.by Michael Hamburger)

”The Book of My Enemy Has Been Remaindered” by Clive James (in dialogue with poetic elegy)

”The Death of Clive James Has Been Postponed Again” by Daniel Bosch (in dialogue with poetic elegy)

“Kaddish” by Allen Ginsburg

“Elegy for the Personal Letter” by Allison Joseph (elegy for an object

“I Thought I Could Not Be Hurt” by Sylvia Plath, an elegy to one of her own paintings after her grandmother smudged it slightly

"Elegy for a Child" by Gregory Orr

"They Said Your Father's Griefs" by Jean Garrigue

“Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat Drowned in a Tub of Goldfishes” by Thomas Gray (elegy with relation to ode)

“Elegy for a Living Mother” by Renee Agatep (elegy with relation to ode)

* It’s interesting to contrast this with an ode, or think about what it means to elegize the living, both as a strategy of subversion and resignification.

“Didatic Elegy” by Ben Lerner

“Elegy to Ramon Sijé” by Miguel Hernández, which doubles as tribute to the town Orihuela

”Elegy for the Quagga” by Sarah Lindsay (elegy for place)

”Elegy for the Animals” by Sarah Lindsay

"Deer Ghost" by Joy Harjo

“Provenance: A Vivisection” by Sally Wen Mao (self-elegy)

”Until My Resurrection” by Cesar Vallejo (trans. by Scott P. Cunningham)

”The Living Are Legends” by Daniela Danz (self elegy)

”Tabernacles Will Turn to Sieves” by Diane Mehta

“Elegy for Living Alone” by Elizabeth Theriot (elegy for part of self)

“Elegy for String Orchestra: In Memoriam Rupert Brooke" by Frederick Septimus Kelly

”Resistance” by James Hoch

”Sonnet” by Stanley Plumly

"The Language of the Dead" by Thomas McGrath

"An Early Afterlife" by Linda Pastan

”Life, Do Not Abandon Me” by Magda Isanos (trans. by Christina Tudor-Sideri)

*

Strand, Mark, and Eavan Boland. The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms. W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

Shara Lessly. "Split the Lark: Shara Lessley on Contemporary Poets, Some Memorials May Be Unstable: Elegy & the Absurd". West Branch.