Poetry Daily published a beautiful excerpt from Adam Zagajewski's Slight Exaggeration and I need to save--to savor and swizzle-straw--the parts that struck me. So I've kept the saliency in conversation with poems that run back through my head, run back on railroad tracks as if scheduled.

“I won’t tell all regardless. Since nothing much is happening anyway. I represent, moreover, the Eastern European school of discretion; we don’t discuss divorces, we don’t acknowledge depressions. Life proceeds peacefully around me, a gray and exceptionally warm December outside my window. A few concerts.”

Encounter

by Czeslaw Milosz

We were riding through frozen fields in a wagon at dawn.

A red wing rose in the darkness.

And suddenly a hare ran across the road.

One of us pointed to it with his hand.

That was long ago. Today neither of them is alive,

Not the hare, nor the man who made the gesture.

O my love, where are they, where are they going

The flash of a hand, streak of movement, rustle of pebbles.

I ask not out of sorrow, but in wonder.

“A poem is like a human face—it is an object that can be measured, described, cataloged, but it is also an appeal. You can heed an appeal or ignore it, but you can’t simply measure its meter. You can’t gauge a flame’s height with a ruler.”

Tortures

by Wislawa Szymborska

Nothing has changed.

The body is susceptible to pain;

it has to eat and breathe the air, and sleep;

it has thin skin, and the blood is just beneath it;

an adequate supply of teeth and fingernails;

its bones can be broken; its joints can be stretched.

In tortures, all this is taken into account.

Nothing has changed.

The body shudders as it shuddered

before the founding of Rome and after,

in the twentieth century before and after Christ.

Tortures are just as they were, only the earth has grown smaller,

and what happens sounds as if it's happening in the next room.

Nothing has changed.

It's just that there are more people,

and beside the old offences new ones have sprung -

real, make-believe, short-lived, and non-existent.

But the howl with which the body answers to them,

was, is and ever will be a cry of innocence

according to the age-old scale and pitch.

Nothing has changed.

Except perhaps the manners, ceremonies, dances.

Yet the movement of hands to shield the head remains the same.

The body writhes, jerks and tries to pull away,

its legs fail, it falls, its knees jack-knife,

it bruises, swells, dribbles and bleeds.

Nothing has changed.

Except for the course of rivers,

the lines of forests, coasts, deserts and glaciers.

Amid those landscapes roams the soul,

disappears, returns, draws nearer, moves away,

a stranger to itself, elusive,

now sure, now uncertain of its own existence,

while the body is and is and is

and has nowhere to go.

“ Musil wrote a beautiful speech when Rilke died—he was among those who recognized the poet’s greatness early on. I also found a description of the tragicomic talk Musil gave at the Congress for the Defense of Culture in Paris in June 1935. He had no idea that the Congress had been organized by the Communists, and thus only Hitler’s system was open to criticism: the Soviet Union was off-limits. But Musil defended the artist’s individualism and warned against the collectivism emerging in various European nations. He insisted, too, that there was no connection between culture and politics, that culture’s very existence depends upon some delicate, capricious, unpredictable element, hence even a decent political system won’t automatically produce great art..... ‘The Man Without Qualities’ operates on an entirely different principle; all the references to political and philosophical reality have an intermediate character, they’re mystical, allusive. Musil was captivated by ‘der Möglichkeitssinn,’ the sense of possibility, by whatever happens exclusively in the conditional.”

“I can’t write poems in recent weeks either. It’s not the first time it’s happened. And it’s not worth going on about either. There’s not much to tell. Karol Berger found something Victor Hugo said on the subject—he told me about it as we were walking in Paris, in the 16ème. When someone asked him how hard it was to write poetry, he answered, “When you can write it, it’s easy, when you can’t, it’s impossible.””

Plans, Reports

by Adam Zagajewski

First there are plans

then reports

This is the language

we know how to communicate in

Everything must be foreseen

Everything must be

confirmed later

What really happens

doesn’t attract anyone’s attention

“An extraordinary person, an exceptional mind once lived there, someone who defied the tendencies of his time (but who said we should yield to the age’s tendencies?), who tried to synthesize all the events and ideas of his historical moment. He was the only serious intellectual I knew who studied even the Harry Potter series. What for? To find out what children were reading, what draws them, and what it says about a shifting world. He good-naturedly acknowledged Harry Potter; nothing bad in it, he said in his baritone. He was more like Thomas Mann than Robert Musil: only what really existed stirred him, not Möglichkeitssinn, not the sense of possibilities. He didn’t lack for mystical appetites, but his mysticism fed on the yeast of reality. In the long poems he was a shark. And a shark in his reading, devouring theology and philosophy, poetry and history. I think of this when I meet young poets on both sides of the Atlantic. Sometimes they seem to notice only the most recent issue of the trendiest poetry journal. As if poetry weren’t—among other things—a response to the state of a world that shows itself in a thousand different forms, the grief of the unemployed man sitting on a park bench on a lovely April day alongside philosophical treatises and symphonies.”

In Black Despair

by Czeslaw Milosz

In grayish doubt and black despair,

I drafted hymns to the earth and the air,

pretending to joy, although I lacked it.

The age had made lament redundant.

So here's the question -- who can answer it --

Was he a brave man or a hypocrite?

“And once again it was June—mild, long, slowly fading evenings, evenings promising so much that no matter what you do with them, you always receive the impression of defeat, of wasted time. Nobody knows the best way to get through them. March straight ahead or maybe sit at home before a wide-open window so that the warm air, saturated in the sounds of summer, may permeate the room and mingle with books, ideas, metaphors, with our breath. No, but that’s not right either, it’s not possible. You can only mourn them, those unending evenings, mourn them when they pass, as the days grow shorter. They can’t be seized. Perhaps these long June evenings can only be perceived by way of regret, remembrance, nostalgia. They can’t be plumbed: you’d need to head for the park, one foot in front of the other, while sitting simultaneously on the terrace and listening to the voices of the city fall still as the last blackbirds sing … But that won’t do either. Birdsong has no form, no adagio, no allegro. In a detailed study of music, a certain philosopher once observed that “nightingales don’t listen to other nightingales sing,” only somewhat exalted people do. Hence you can only tear yourself away when you get bored (let’s be honest here). Whereas a musical composition, subject to the discipline of form, forestalls the moment of our boredom...”

Indiscretion

by Ewa Lipska

Had she busied herself in time

with the systematic counting

of ship screws

it would not have come to this—

indecent acts of poetry.

“And just when it died, I was born. At dusk, in June, that distant life, which no longer exists—except perhaps on old postcards, where it’s diminished, turns into caricature, on postcards where we find, peering out at us, preposterous gentlemen with overripe mustaches and ladies with frantic hats upon which the gardens of Semiramis blossom, so that we can’t see ourselves in them at all. Only on these does it secretly appear anew. If only we could listen more carefully, look more closely … Someday something will happen, the inner reality will stand revealed. At the same time I realize that this sense of mystery, of secrets dwelling in these streets, in this park, is fleeting and hard to defend. If someone were to ask me ironically, “Mr. Zagajewski, what actual mystery do you have in mind?,” I’d be hard-pressed to answer. I also know that there are people, some of them highly intelligent, who can never be brought to acknowledge the postulate of a mystery hidden in a city, or a park, or a quiet street at dusk. No, they’d say, everything can be checked and measured, so and so many bird species make their home in the park, including two subspecies of woodpeckers, along with twelve squirrels, maybe two martens, and five bums.”

Forget

by Czeslaw Milosz

Forget the suffering

You caused others.

Forget the suffering

Others caused you.

The waters run and run,

Springs sparkle and are done,

You walk the earth you are forgetting.

Sometimes you hear a distant refrain.

What does it mean, you ask, who is singing?

A childlike sun grows warm.

A grandson and a great-grandson are born.

You are led by the hand once again.

The names of the rivers remain with you.

How endless those rivers seem!

Your fields lie fallow,

The city towers are not as they were.

You stand at the threshold mute.

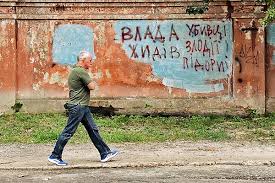

“This crippled city requires not only sight and hearing, but imagination. Imagination, it’s true, bears only upon absent, distant places, as Proust says; we can’t imagine the street on which we’re actually walking, the room in which we’re standing, the person with whom we’re talking. But Proust lived in the classical era, before the disaster; he couldn’t foresee that one day there would be half-abandoned, half-existing cities, cities covered with a tarp of ugliness, cities lost and half-recovered. He couldn’t foresee that in such cities imagination becomes—must be—yet another sense, half imagination and half sensory apparatus, since here the everyday medically and empirically established senses don’t suffice, they must be supplemented by a half-shut eye, intuition … He couldn’t foresee our journey to Lvov, to a city that belongs to no one, not to those who left, nor to those who remain, and thus demands a new type of imagination. I didn’t speak at such length, of course, I couldn’t develop my argument, I was much more abrupt and emotional, clumsier, no doubt. Only now, as I sit in my room listening to music, can I write down what I really meant to say, conquering my eternal esprit d’escalier, I improve the imperfect reality of that evening when we sat in the cellar of that restaurant near Academic Street (the prewar name) in Lvov. Since after all I write this in order to revise my curtness, my clumsiness, to convert my scowls and half thoughts into longer, more convincing sentences.”