1. The loss of memory in poetic subjects

There are many ways to lose a mother. Alzheimer’s is a particularly difficult journey of loss, a grief that begins before the death of the body—a loss that demands reconciliatory gestures from the poet, as James Meetze’s Phantom Hour has demonstrated.

Erin Coughlin Hollowell’s Every Atom begins in relation to those ghosts, or to the empty, unremembered spaces. Dan Branch notes that Hollowell’s mom’s mental capacities were declining as Hollowell wrote this book. And she did not write it from a distance—instead, Hollowell gave up a writer’s residency in Washington State to assist her father in caring for her mother. The book is dedicated: “In memory of my parents, Leonard James Coughlin and Mary Louise Coughlin".”

Although the poems place the mother in landscape, or navigate her absence by landscape metaphors, the tone often wanders into the ethereal, which is to say that ethereality might be a coping mechanism in poetry: how language of presence is displaced by language of absence.

Most interesting to me was the role played by metaphor, imperatives, and conditionals across the breath of this collection.

From the outset, we know the narrator is trying to relate to ghosts, or finding a space for them in ordinary life. See “The last scud of day”:

I brush away the hours

like the smear skids of eraser

left over from a project that went

from unwell to undone. Words

scrawled over the ghosts of others

and then rubbed away again.

We suspect the work of finding meaning requires a relation to hieroglyphs, to reading the signs in surrounding objects, as in "Night of the few, large stars," which ends with the poet trying to make sense of constellations:

Three stars:

a king, a shadow queen,

a child who is lost on purpose.

It is images and metaphors—rather than people, loved ones, stories—that provide mooring in these poems. And Hollowell’s images are powerful; they are hinges for the poem, spaces at the threshold of something opening or closing. I held my breath midway through "The palpable in its place and the impalpable in its place" when I came across this image:

The window blank with light.

And because I find complicity more compelling than innocence, I valued the way the poet unpacks (or carries) guilt in these poems. It is a complicated guilt—a human one. "Waits by the hole in the frozen surface" begins with waiting for a memory, evoking the absence of both memory by implying a sort of loose complicity in the narrator's inability to remember. O reader, you must remember this book is about a mother losing her memory and dying—but we are also standing on a frozen lake, somehow, waiting for something to explain the hole in the ice:

I remember kneeling before my brother's coffin

but of my mother's grief there is a hole, as if

I've taken scissors and neatly cut her from the day.

Hollowell returns to this metaphor, to this hole in the ice of the lake often, as in "Life whenever moving":

Imagine your mother

was a turtle. Her great

three-chambered heart

beating between two

hardnesses. Her legacy

a sandy hole or a shade

on a riverbank. And you,

left in a leather purse

of an egg.

This poem moves through imperatives to imagine--to imagine the mother as turtle, oyster, cicada, to fill in the whole with an image---and then to relate to it, to find meaning about the daughter in relation to that image. And I keep thinking how the imperative can, in poetry, serve as a vehicle for incantation, a spell the poet wants in order to inhabit the raiment of liminal space.

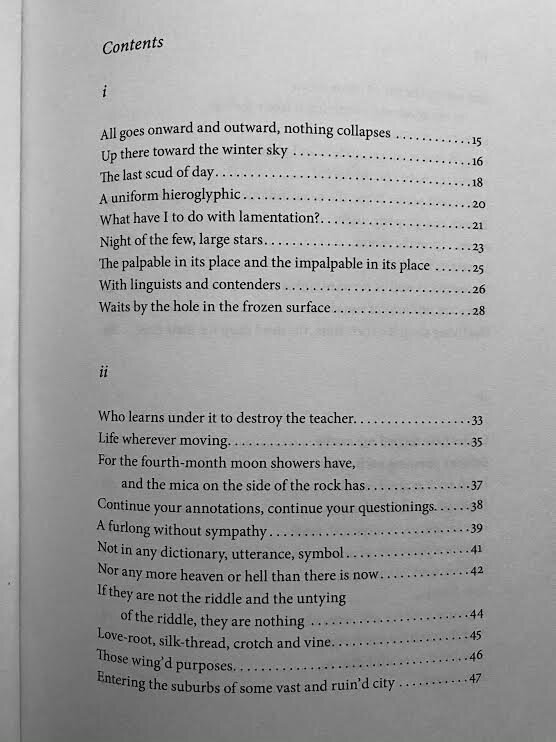

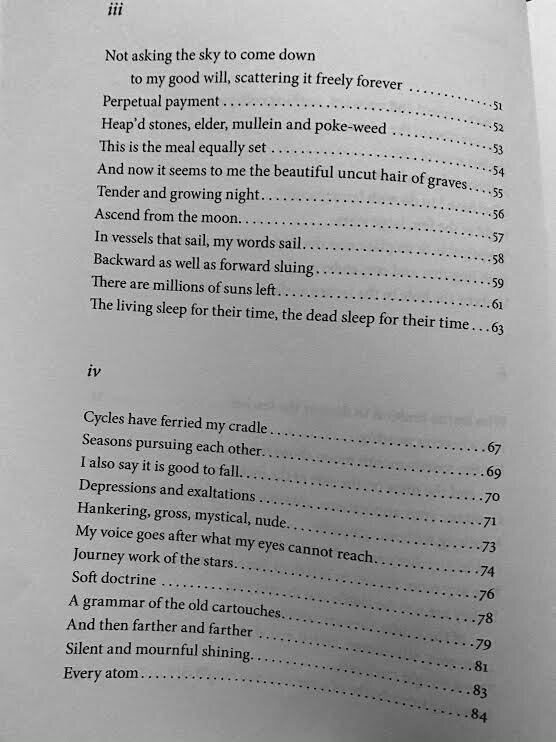

3. The poetry of titles

So many questions lately in the poetry community about titling poems—and how titles work best in a collection— Hollowell’s titling is haunting; the titles can be read on their own, as a poetic mode. Titling does the work of conveying tone in this book. Notice how she does this rare thing, namely, enjambing the titles, allowing them to stretch across the page and then break, as in:

“For the fourth-month moon showers have,

and the mica on the side of the rock has”

which begins with a powerful image, and it’s relation to imperative:

shine, glisten like that sleek lick

of damp left behind by a snail.

These titles are conversant with the poems, rather than nominative—they do not name what will happen so much as present the conditions under something could occur. They describe a mode rather than a theme.

4. Hollowell’s conditional mode

Also: this sense in which the metaphors, themselves, are imperatives for the poet.

And how close these metaphor-imperatives come to the conditional form, or how the conditional, itself, is implied in them—though also evoked directly, as in “Perpetual payment,” which begins:

If you could unlock the box

within the box within the fist

of meat that beats to its mechanized

meter, you would find my father.

The poem progresses through six quatrains to end in a reversal, a resistance to both the father’s explanations and, in a sense, the stories themselves:

My father’s stories built the house

we set on fire and fled from. My father’s

stories built a plucky woman on a train

that none of us have ever met. Somewhere

the bear is still bleeding. Somewhere

that mother is still riding the train.

Maybe stories are not helpful. Certainly metaphors and conditionals seem like more significant terrain for this particular grief, this attempt to live with a loss. Rather than construct a new mythology to assuage grief, Hollowell remains restless, eyeing the hole In the ice, the moon, every atom—eying them loosely, tenuously, as possibilities rather than explanations.

I love this. I could say more—o I could burn the day with details—instead I rest in this interesting approach to what is not quite elegy, or what edges lament without settling for the narrative that allows lament to grow its iconographies. What if mom was an oyster? Who would her daughter be, then?