1.

“I come from a place where the hand of the wind gives shape to everything. All plants are in permanent sway and bow to it, trees bent over, all objects necessarily weighed or battened down, stillness nearly unheard of except in those green-skied moments before the tornados come.”

-Anne Boyer, “The Heavy Air”

2.

Simone Weil uses the expression airless-merry-go-round to describe Rose Luxembourg’s efforts to include female bodies in Communist Party policies and platforms. Weil means to address the CP’s abandonment of female-gendered bodies, and her words bring to mind a carousel in a park with the women falling off horses, smiling, lying like dead flowers in circles for men.

I love Rosa Luxembourg. And Weil. And carousels which are not airless.

3.

In Bucharest, Paul Celan knows his parents are dead; Bukovina holds nothing but ghosts and survivor’s guilt. As for the subject, the survivor does not have time to ask which part of self has been left, or what will continue. He writes a few prose poems which his friend Petre Solomon admires. In one, the narrator describes a gold chandelier with thousands of arms that will save him and his Jewish friend, Rafael:

You will climb up one of its arms so that, once I have lifted it high up in the air, you can fasten it on to the sky. Before the break of dawn, people will be able to save themselves by flying there. I will show them the way, and you will receive them.

I climbed on one of the arms, Rafael moving from one arm to another, touching them in turn, the chandelier began to rise. A leaf settled on my forehead, right in the space where my friend's gaze had touched me, a maple leaf. I looked around: this cannot be the sky. Hours pass and I find nothing. I know: people gather below me on the ground, Rafael touched them with his slender fingers, and they too rose towards the sky, and I still have not stopped rising.

Where is the sky? Where?

Something appears in this translation which does not exist in the original Romanian text.

The way air nestles inside despair: a gift of translation.

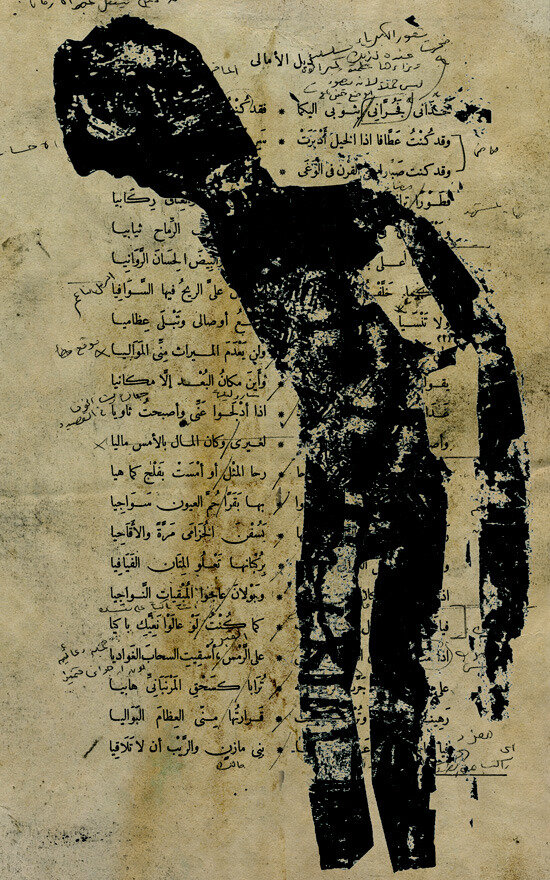

Elegy of Malik Ibn Ar-Rayb (2010) - Iraqi Artist SADIK KWAISH ALFRAJI (صادق كويش الفراجي)

4.

Do not ridicule yourself if you are incapable of providing proof. Air is air and does not require a certificate of blood. Do not regret! Do not regret what you missed when you took a nap; recording the names of invaders In the book of sand. Ants narrate and the rain erases. When you wake up, do not regret that you were dreaming and asked no one: Are you a pirate?

-Mahmoud Darwish

It is difficult to stop reading Sinan Antoon’s translation of Mahmoud Darwish's In the Presence of Absence (Archipelago Books), first published in Arabic in 2006.

Darwish would die two years later, and the book, itself, was written by a man who sensed this: a poet staring at his end. By this point, Darwish had already come close to dying twice—which he wrote about in his epic poem, Mural— but here, in the presence of his own absence, "the living I bids farewell to its imagined dying other in sustained poetic address divided into twenty untitled sections," each of which addresses a theme from the poet's past.

Drawing on the classical Arabic tradition of self-elegy, Darwish addresses a “You” which is both spiritual and embodied, both placed and displaced, a continuous unsettlement.

But it was Malik Ibn Ar-Rayb, a Muslim Arab poet from Tamim in Al-Basra, who introduced the self-elegy as a poetic form in 676 AD. Returning home from a trip with Saeed Uthman ibn Affan, the 3rd caliph’s son., Ar-Rayb was bitten by poisonous snake. Anticipating his own death, he wrote his own elegy.

Not entirely “a certificate of blood”: a poem as a form of evidence which repudiates the elegy others wish to lay over a body silenced by death.

5.

“What is overhead is not exactly free; it is merely unevenly owned. Nations claim airspace, militaries plot no-fly zones, and clouds reside without permits. Ideas are the correlate of air. Clouds are air’s objectifications, and, as perspiration and respiration, air is where effort goes once our effort is spent. This crowded air is the stage of everything dematerialized’s abiding dematerialization. Everything solid melts into it.”

-Anne Boyer, “The Heavy Air”

6.

“Ar-Rayb conceives his own death and, under fear that he will inevitably cease to be, starts mourning his own loss. He invokes his poetry to help him visit his far away home to meet his family, kinsfolk, beloved, and people, and he implants into the essence of his verses his happy, honorable, and worth-remembering past. His mind is overloaded with thoughts on unfulfilled desires and dear people, animals, places, deeds, and qualities which his fear of death generates and of which death will deprive him. As he recalls his homeland and beloved, he explains the heroic and religious motives for which he left his sons, fellow people and possessions, while at the same time wishing that news of his dying would be passed back to home. The poem’s varied elements and the poet’s numerous superficially paradoxical thoughts simultaneously coexist, each leading to, and led to by, the other in the sense of Freudian association, as if they are all felt at once. He thinks of past and present altogether, and momentary sensation overlaps and intermingles with recalled elements.”

-Nayef Ali. Al-Joulan, “Aesthetic Dying: The Arab's Heroic Encounter with Death” (PDF)

7.

In an end-note, Sinan Antoon offers insight on a particular word’s translation. While Mahmoud Darwish used the word "barzakh" (which the translator elects to render as "threshold"), the original word invokes the eschatological word for the boundary between the human world and the spiritual one.

It is a word often used “by mystics.” It is a border of sorts.

8.

Mahmoud Darwish describes his childhood, the magic of discovering words, the beginning of the poet’s fascination with language. As he learns to write words in school, he finds that they establish a relationship:

“The sky, too, becomes one of your personal belongings if you do not misspell it."

And later:

"You become words. ..you do not know the difference between utter and utterance. You will call the sea an overturned sky."

9.

I can’t find an order when trying to compare the sky to the ground. The horizon is an illusion. It is a lie. Sky and earth remain disconnected, never quite touching.

10.

I stood on the bridge in the sky on the bridge between

Two buildings at the second floor but in

Between the buildings so in neither one

But in the sky on the second floor in the sky

Barely I had just barely stepped from the

Nordstrom to cross to the food court barely and I

-Shane McRae, “Between”

You can read this poem in its entirety at Yale Review.