1.

As the child of Eastern bloc defectors in Alabama, I grew up forbidden. True things hid inside the mother-tongue that kept the heart secret. I blame my parents for my fascination with walls, fences, boundaries, barriers. I blame the sky for beguiling me. I blame language for carrying oceans. I blame myself for everything else.

2.

It is April 2020, the first month of pandemic; the book in progress, sidelined by childcare. Time coils, crackles, loosens: I am torn between restlessness and the recklessness, the loneliness of being housebound with three children. Solution: leave, run, escape by packing kids into the car and roaming backroads, our eyes peeled for meadows, space outside the choir of sirens arriving and departing the three hospitals near our house.

Forty miles outside the city, a locked green metal gate appears, the road behind it winding towards hills. I tell the children this is it. I park along the edge of a ditch. The son notices the sign says NO TRESPASSING. He misunderstands the invitation.

"There is nothing forbidding here," I assure him as an ordinary yellow butterfly settles on the gate, two long metal beams shaped like wings on a hinge with a side padlock. It is inviting. It is idyllic. It is the middle of nowhere: what a map calls Chalkville.

I have more to say but I keep the other things to myself. I turn the word bucolic on my tongue but do not offer it to the children. I keep bucolic quiet, preserving its connotations from their curiosity. I save this word for a poem I haven't written. The poem is always there, simmering beneath the surface. At this point I care more about the word than the clamor of three children who make buzzing sounds in the absence of bees.

Look, I have done worse than what we are doing, I tell myself as we scale the gate, throw our legs over the top, drop our backpacks to the ground in different pitches of plunk. The sun lengthens our shadows. The sun sprawls across shrubs like a mother at the beach who silences the world by unimagining it's existence. We walk past a paved driveway lined by trees, soaked in fresh chirps, a tiny creek dawdling to our left.

"It's not even a real creek!" the youngest announces, "it is a tod-dler creek." (She is the proud older cousin of a toddler.)

To the left, the son identifies a patch of cultivated daffodils--definitely planted, he confirms, not wild. Brown hair crawls over his shoulders like uncombed snakes. His hair is a separate wilding. "This place had an official gardener on staff at some point," he says. He can tell from the layout.

The unreal creek toddles along with us for ten minutes, rounding a curve, passing a monstrous patch of kudzu, at which point, a silhouette of a steeple appears in a vague forward, also known as the future, and it rubs against the past, rubs against that once when the middle daughter smelled a rotting rat beneath the porch. Now her eyes narrow. The middle daughter expresses concern about the vast kudzu kingdom--its hollows and hills, the shape and dull rolling--clearly haunted. She has a strange feeling about this place which strikes me as hopeful; hope being the condition of having and holding strange feelings close to our hearts.

When she lowers her voice to a whisper, I follow suit. "Micah is being exemplary," I whisper, stunned by how the change in volume changes the hue of the green things. This feels appropriate, the awe-filled tone correct when addressing a kudzu patch. It is respectful.

"But you are confusing awe with foreboding," my son corrects. He is very articulate and a frisbee of meaningfulness at odd moments. He is not the voice of reason, though he resembles this voice from a bird's nest.

"No," I insist. "This is the Church of Wandering; and there is the steeple. Every stop along the way may be part of the passion or else a tussock where a donkey paused to eat clover as a god thought his cross-thoughts. Surely we are monks in this."

I consider what it means to be a monk in an unforbidding place as we pass around a water bottle and start walking again. I resist the temptation to draw an analogy between sharing bottled water and drinking from the same chalice which might contain the blood of a man who is no longer alive. I maintain a relation to abstraction: we are monkish.

3.

We approach the ruins of a stone chapel with a hole carved by a wrecking ball in the front. "Something massive must have been removed," I say.

The son suspects it was a big old bell: a bell-tower with an open wound.

The urge to write slams into me like a train.

The kids want to keep going. One has a caterpillar on her shoe.

"But we are monks," I say, "this is our discipline--to bring all possible attention to bear on that gape-mouth wound." Life is a form of poetry, and poetry is a form of discipline, namely, the focus and attention of one who wants to be raptured. The methodology is to see what lies before us with the lover's insatiable eyes, the gaze that can't touch or taste in moderation.

The son makes disgusted noises.

I tell them to go ahead and ramble without me.

A purple flower lifts her anonymous face from a crack in the pavement. There is this breeze, I think, which is not quite a wind.

"What is Mom doing?" the son groans.

"She is staring at that hole with all her mightiness!" the youngest declares.

"Oh look at that vine climbing through the window's eyeball," the middle daughter warns--"Oh this place is for sure haunted by horrors happening to children. It's like a tinfoil pinwheel."

Her simile disarms me. A good simile is a light that reveals without sterilizing the room for surgery. It is visible--it offers a tactile picture, its plastic tinfoil physicality embodying fear--not the abstraction but the cheap kitsch of its connotations clinging to what should be fun. And isn't it funny how so much of what should be fun in childhood is actually terrifying?

I want to come back to the hole in the wall or the wound in the bell-tower, specifically, the location of this wound over the larynx of the bell-tower's throat. Is a bell-tower without a bell still a bell-tower?

When the son expresses hunger, I groan. The burden of childcare: entirely mine during pandemic. A childless female friend celebrates the extra time at home: "I'm going to finish my book," she announces. My husband has taken over my study to work from home.

I am somewhere between a steeple and a simile, thinking about mothering and losing your voice in winter and whether bells are like children who have disappeared behind the tall grass growing over the tennis courts. Whether children are closer to bells than missing balls. Only when faced with the weed-smothered tennis courts do I begin to wonder where we are. Why the tennis court nets are doused in vines. Why the children are hesitant. And I think about James Longenbach, who said a poem's power comes from its ability to resist its conclusions while being pulled toward them. I think about what it means to be haunted or remembered--and why the middle child is the one who keeps mentioning it. So much hinges on how we carve implication. Or what we want from the landscape.

“The Word Is a Lamp Unto My Feet….”

4.

Crouched beside the tennis court, a long, ranch-style brick building waits, its edges thick with the white blooms of privet, the flowers open, sickly fragrant. The scent is too sweet, almost odious.

The children wander in circles, back back to the chapel whose entrance way is now visible, a hot pink, purple, orange and green clown face spray-painted across the wood front doors.

"Teens must have been here," my son says. He is a teen, and therefore an authority on teen-ness. He helped spray-paint a mural on a city wall last year under quasi-legal circumstances.

Above the clown's fluorescent leer, an engraved stone plaque makes its claim: Thy word is a lamp unto my feet.

"It doesn't make sense," the youngest says, "unless this was a night-night church and people needed night-lights to find it?"

The night-night church with a clown mouth and a wound in the bell-tower's throat.

There is another brick building across an empty parking lot. There is a pink flowering dogwood holding an umbrella over the shoulders of a cairn. There is no one here except us and the paint-tracks of teens and the scandal of empty buildings you can't see from the road.

Micah runs her eyes over the terrain. She reminds us that something awful was done here. She can sense it in her tummy like that time she ate too many roses off the brick wall and had to go to the doctor who said parents should know better than to let kids eat roses.

The middle child has carried this guilt for years: "You told me not to eat roses, Mom, but you never told the doctor that you told me."

I remember the doctor was pregnant, tired, probably not even listening.

I ask my daughter to let that go, just drop it in the Church of Wandering's invisible confessional where all is forgiven but not forgotten--all is important, luminous, but also one single impression. Not the whole story.

This, too, is a discipline. I have learned to give joy my full attention from failure, particularly, my inability to find joy in home decorating, in settling, in using the scripts shared by friends for recipes, good workouts, affirmations, crunches. As a child, I was the joyfullest melanchole in Tuscaloosa County. Now I am mothering it's worried expressions.

My son rolls his acorn-eyes as I sit on the last moment this rock could be called a step and open my notebook.

"What happened to wandering?" he asks.

His voice fades. I wander inside. I wander off in my mind.

"You can still eat violets," I tell the children. Violets are packed with vitamin C and stardust. I gesture towards a clump nearby.

A purple clover actually resembles the instant before black hole swallows matter. I take notes. I confess. Here's what I know: it is easier to parse birds than to discuss how a face turns ominous or the way bricks change the tenor of nearby dahlias or the mist in his eyes when he kissed me. The not-blue of it.

The notebook carries the conversations no one wants to have with me. My commitment to the notebook —and to writing — includes a commitment to these conversations that raze me, that raised me, that keep razing and raising the roof. I am happy when writing these things which make the world in which no one talks about reality, about what it means to live in bodies which betray us, a little more tolerable.

The notebook is a secret closet where I go to resolve things.

The notebook is the stable where the horses I've invented by discipline wait for me to ride them.

"I'm really scared," the middle child says. Her voice is trembly, willow-like. She wants to go home and maybe come back with Daddy. There could be teens hiding in the buildings. No one knows where we are.

Where are we?

The wind lifts the hair round her face and I think if any of us can read the sky, it is this one--it is this child, the little limner. I give in.

5.

Two days later, we return with my husband, official Daddy, paterfamilias, patriarch in residence.

"Since I'm driving," he says, "I need to know where we're going."

I say we don't know exactly. Near Chalkville. It's a place that existed with a steeple and a creek and tennis courts. Someone may have stolen the bell. It's behind a padlocked gate. It has thickets of rolling kudzu. It's a room in the world we want to know further. It's somewhere on this road if we keep going.

My husband merges, follow directions. When the metal gate appears, he pulls in and parks close to it. He takes his time collecting blankets, books, apples, extra water, a few beers.

A white truck passes slowly on the county road, looking official.

The son says we should probably hurry and jump the gate and get in there before someone stops us. Girls beat him to it. I follow.

As my husband locks the car behind him, the white truck reappears. The kids and I watch from the other side of the gate, safe within the Church of Wandering, as the white truck parks next to our car and an alarming white male emerges wearing a t-shirt tucked into his khakis.

"This is state property!" the man yells. "I am the city manager! It's a felony to trespass on state property!" He is walking and yelling in tandem, like sirens.

I remember sirens with no stitches between screams.

He waves his arms for me to come back: "Those kids have no business back there with Satan worshippers! There are Satanic people that go back there and I arrested two last week!"

My husband lowers the rim of his baseball cap until I can't see his face as he asks the city manager what this place was, or is, and why it belongs to the state.

The manager spits, his face flushed, camellia-like, two red dots on his cheeks resembling those of the church-going clown painted over the doors. "This was the home for Bad Girls! They kept misfitted daughters here!"

The middle daughter steps on my shoe, says she knew it. Didn't she warn us that awful things happened to kids here?

The son is as tall as the city manager, or so he is thinking, when he straightens his posture and notes: "It's hard to see the No Trespassing sign from the road. We must have missed it."

A blue truck honks three times in passing.

It is unfathomably sunny. I imagine thorns growing from teeth.

Something inside the city manager is rumbling, changing, struggling with something outside the city manager and it's impossible to name either thing--the most I can do is note the conflict.

"Look over there!" the manager points to the massive kudzu patch. "That is a crime! That was a Confederate graveyard until contractors used it as a dump for their clean-up."

The middle daughter says she knew it.

The manager asks what she knew.

The son says no one knows anything anyway we should just leave. This isn't fun anymore.

I tell the manager that we just wanted to have a family picnic, experiment with family values in a place we'd never explored.

The manager approaches me with his pointer finger directed at my chest: "I hereby declare myself a constable. As a constable, I have the capacity to haul you into jail and arrest you for a felony."

Constable. Capacity. Arrest. The last word isn't unfamiliar.

The littlest daughter tightens her grip, the sweat between our hands sealing us closer, a diluted glue. I want to comfort the kids and my man, but I'm mesmerized by the shape-shifting: how the manager has morphed into a constable without any strobe lights or magic smoke, only the power of a few words thrown from his mouth.

I hear myself saying I have never met a constable and how nice to finally meet one. What feels like magic may be the beard of a breeze my daughter construes as haunted. Or just a man using words to reinforce walls used to imprison young girls.

The manager's finger descends, the muscles in his neck soften, he says this whole place is haunted and we don't know the half of it.

My husband picks a tendril of honeysuckle vine and puts it on the dashboard as he repacks the car.

A brown chocolate labrador retriever appears from nowhere and nudges the dirt near the gate with his nose. The labrador lacks a collar. We don't know how long he's been here. Even the patch of white daffodils seems ominous--it must have been planted by the people who worked at the home for bad girls. The daffodils watched a graveyard get ploughed over.

Since the manager's abracadabra, I wonder about signs, things I missed.

The middle daughter didn't miss any signs.

The littlest knows toddlers, the oldest knows teens, the middle one knows ghosts. Each has their angle of insight. I am here for the poem intended to house the word bucolic.

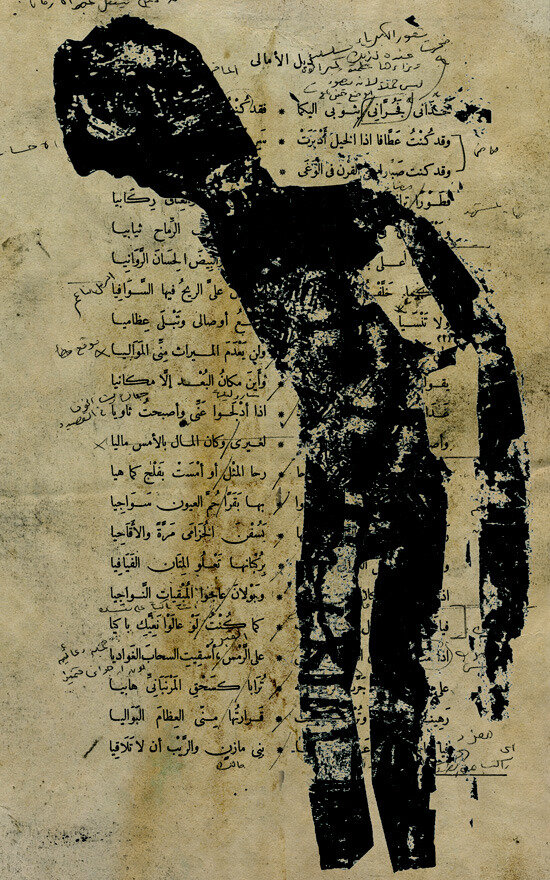

“When the past is not preserved but discarded (the way you might clip hair or fingernails), the dead have fallen out of favor. They find themselves in the position of an aggrieved minority. They lose the right to our attention (and the ability to dodge said attention); they no longer have a say—they are remembered as others see fit.”

- Maria Stepanova in Paris Review. Her words came back to me when I thought about how the graffiti at the detention center demanded memory, refused burial of the past.

6.

In the car, it is quiet. I lay the honeysuckle over my left shoulder and let it slither across my arm like a feather boa or an honest snake. I let it settle into the snake it wants to be….."So where were we?"

I ask this knowing where we were is never far from where we are.

The map shows nothing. I search my phone for youth prisons and Chalkville. The words open it up. Known locally as the school for bad girls, the Alabama Training School for Girls housed "incorrigibles", "delinquents", or "waywards", most of whom were never formally charged with a crime. It was constructed in the 1930's to hold more than one hundred and fifty youth with non-criminal violations. The Works Progress Administration helped dig the swimming pond and design the recreation areas for what would later be known as the Chalkville Detention Center.

In the ranch-style dorm building, there is a time-out room with a heavy metal door and tiny glass hole through which guards could view the girls placed in solitary confinement. Metal bunk beds lined the walls of the dormitory, and the heavy metal doors to the windowless sleeping rooms were locked at night.

We didn't get to explore this part. I learn about it by doing what a poet does when she finds a plant she can't describe--I looked for the root word, the etymology, the ways this plant had been used by others, the history.

"I knew it," the middle daughter says, her voice low to the floor.

The original bell tower at the “Alabama State Training School For Girls,” which was a WPA project. Source.

7.

Other things I learn and share with the children: the 10,000 pound silver bell from the chapel was probably stolen by construction crews working to clean up the site after a level EF3 tornado with 150 mph winds barrelled through on January 2, 2012. Only eighteen girls and eight staff members remained in the school when the tornado hit during the night. As if by miracle, the dorm housing the residents and staff sustained the least damage. The cafeteria, school, and gym were completely levelled.

In 2001, forty-nine plaintiffs sued the state of Alabama for sexual misconduct involving the state Department of Youth Service's Chalkville Detention Center. The girls revealed that, between 1993 and 2001, they suffered sexual, mental, and physical abuse at the hands of the guards and staff.

The plaintiffs had been sentenced to serve time at Chalkville for shoplifting or drugs or skipping school or behaving in "unbecoming" ways. When their wealthier peers got expelled for similar behaviors, they went to elite private schools.

The line between good and bad in Alabama depends on income and access. None of the girls at Chalkville came from middle-class families. All were raised in poverty. In 2007, the state of Alabama settled the suit for $12.5 million. Each plaintiff received $255,102, from which they were required to first cover the trial expenses and attorney fees.

Things I don't share with the children: S. slept with a guard who promised her early release in return for her sexual cooperation. The guard then proceeded to do the same thing with S.'s room-mate. When S. rejected his advances, the guard added to her work detail and physical exercise regimen. S. said it was easier to just let him screw her--to lay there and watch her life leave its body in suspended animation. The school's superintendent did not believe her. According to media reports, the guard was a great guy, and beloved.

T. was surprised by the attention a shift supervisor paid her. At home, T. felt like an absence, a blank space, a mouth to feed. At Chalkville, T. was fascinating, worthy of a man's time and seduction. There were rumors of other girls he'd seduced at Chalkville. When T. realized she was pregnant, she sued the shift supervisor for paternity.

Across the street in Chalkville’s nice residential, planned communities, other fathers watched football and wept for their favorite teams between fists of beer and french fries.

“Students” at the swimming hole built for the Chalkville Detention Center by the WPA. Source.

8.

In “Faith in the Now: Some Notes on Poetry and Immortality", a lecture on poetry, Jericho Brown says: "I am more interested in learning about why we'd be interested in immortality than I am in immortality itself." This is how I feel about poetry, about the notebooks, about what I want to taste, share, or keep separate. I am more interested in the source of the hunger than the fact of the hunger.

"Writing the poem is how we face the terror," Brown said. In this, "the poem mirrors the process of prayer." And the line-break is like doubt, waiting for the next line, holding faith in what follows from the word, the image, the thing which must be written. This is the thing you must write.

When the kids ask what the girls did that was so bad, I say it wasn't necessarily bad so much as forbidden.

The word forbidden comes from the English verb, to forbid, meaning to prohibit or command against. By the early 13th century, the expression "God forbid" is recorded. In Genesis 2:17, the Garden of Eden contains the "forbidden fruit."

There is no simple answer that doesn't violate human complexity. Nothing is fair but there are moments which teach us to kneel towards them. A story about surviving is complicated by what people expect from survivors, a redemption, an eschatology driven by guilt.

In this pandemic, I don't tell the kids other things I know about words--things I cannot translate into a mother:body.

We are complicit in your silences as much as our statements. See, I am the mother who withholds her own rape from the narrated life she offers her kids. I still cannot talk about it. The words are the metal gate I don't want to explore or open. It is forbidding, though not forbidden. It is something I cannot climb with any word that has ever touched me. It changed my life and yet I cannot help internalizing the belief that my sheer existence in a garden assumed the snake.

The patriarch's story wants my tears tangled in shame. The patriarchy includes allies who believe carceral systems can make us safe. What if the systems intended to save us are the sites of cyclic violence which ensure the continuance of the master's house?

Against the canticle of closed mouths, words can do difficult things. The city manager, for example, became a constable just by saying the magic words. But words cannot do everything. Not for women or girls. Words cannot remake a world broken by its cruelties. They cannot save our bodies. They cannot restore the past or redeem it: at best, words can reveal it.

This essay began with a barrier that felt formal, an inheritance of crossing borders. It progressed through a formal mode, namely wandering, that challenged the essays' linearity by invoking daydreams, unspent similies, strange bells. Now it ends in a space haunted by forbiddenness--a space whose history includes sexual abuse and cruelty at the hands of the carceral state. And silence: my inability to enact sexual violence on the page, my attempt to explain how a woman that jumps fences and risks arrest still cannot speak about rape. And this refusal is also poetry; my poetic "no" is complicated by a sense of duty to children and to our communities.

Rather than pretend to give a "fair account" of the horror that happened in Chalkville (an account I do not believe anyone outside the students is equipped to give), I must foreground the uncertainty, the fluctuating ideals of safety, the unknowable and known in our own adventure as a family--and my continuing silence in certain poems where what I want to say remains what I refuse to be said by.

I am here for the mystery. I am here for the power of words to break bread without breaking bodies. I mother my way through the institutions that fail children, the fences that hold us back from witness, the silences heavy in my own life and blood. I know so little over the long-term, and the poem accepts this uncertainty, this complicity in erasure, this silence of bars.

The poem denies the innocence of culture in its construction of the criminal. It permits the unknowingness which counters the prison industry, the profit made from criminalization of underprivileged bodies.

The patriarchy wants an answer, a clear delineation, an us vs. them which makes war and violence possible. But this is what the poem cannot give you.

I hope we trust the “bad girls” more than we do the system that violates their humanity. I hope we realize that the god of Progress remains fairly Puritan — certainly masculinist — in the US, and the price of neoliberal progressiveness is more boxes, more fake allyships, more therapeutics that lack lived experience, more faith in theory as divorced from life. And because I have no words for the shape injustice lays over recovery, I hope we find a way to poem the most haunted places without shoving ghosts into boxes that suit our pet ideas.

“What do you know, Mom?” A litany of pandemic time, a question I elide, given the limits of what I know, given the forms in which I am known.

I know my middle daughter is the queen of foreboding. My son rarely combs his hair. My littlest daughter forbids her invisible pony from eating apples in the living room. I know the poem wants to touch what lies hidden behind a locked metal gate. I know reality cannot fit the pastoral. I know the word bucolic is still there, in my mouth, where it waits. It waits. Let us wander towards the poem. Let us meet in the ruins of the belltower: the hole in its torn-open throat.

*

[Sources: I have left the names of the Chalkville survivors as initials, though they are easily accessed in public records and news reports. I am grateful to Val Walton's reporting for details on the lawsuit against the Alabama Dept. of Youth Services. Additional details and the stories of plaintiffs were sourced from Amy Singer's "Girls Sentenced to Abuse", Marie Claire, June 2002. And to see the condition of the prison-space itself, to understand what happens to the girls who disappear into the carceral pipelines of American justice, see Kelly Kazek’s photographs of Chalkville, or this video.]