Others pick up words from the streets, from their bars, from their offices and display them proudly in their poems as if they were shouting, "See what I have collected from the American language. Look at my butterflies, my stamps, my old shoes!" What does one do with all this crap?

— Jack Spicer, Second Letter to Lorca

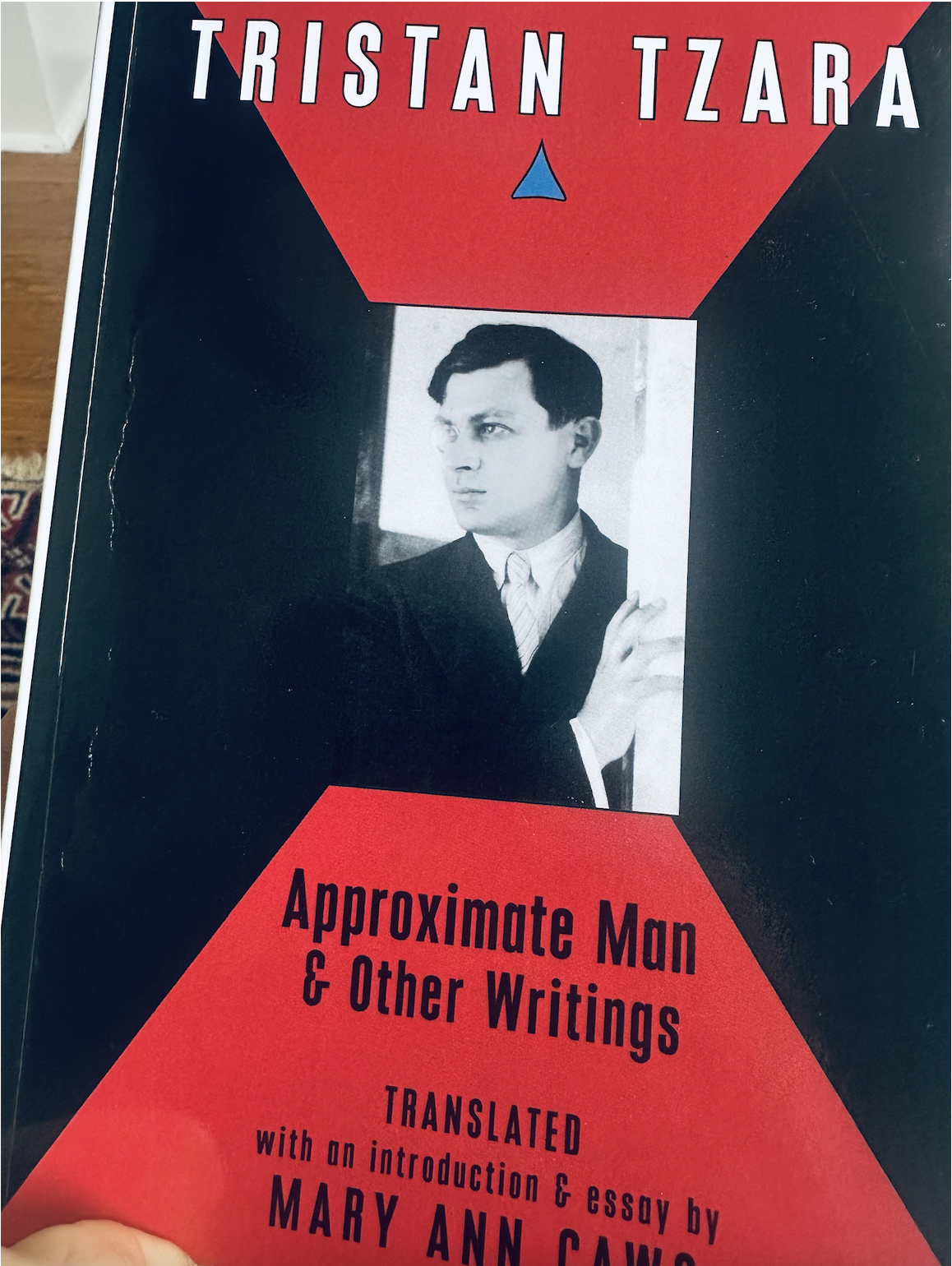

Reading Tristan Tzara’s “Circus,” as translated by Mary Ann Caws, and noticing how frequently he moves from sound to sound, riffing off the homophones and shared energies.

All the colors above are mine, a facet of my plays with language, a subset of looking for pulses that stretch through translations.

Some words cling to each other, and this attachment isn’t a relationship of correspondence so much as a friction that holds possibility to destabilize the separate meanings. One can hear the syllables inching towards each other, at which point the compositional question for the poet becomes one of proximity. Should you, for example, spread out the alliterative nouns across the stanza in order to let them call each other across the field? Or you should you put them in the same line and let them wreak a slight havoc on the senses?

Dada aimed to dissolve binaries.

Tzara’s existence in multiple languages often played into the misunderstanding of idioms and expressions. He kept lists of words and often started a poem from a word-list, looking for the sonic interaction between words, not quite “mining the gaps” (as Rosmarie Waldrop does) but exploding them.

To play with finding a triptych. To pretend that such things are “found”, and “founded.” To go for three as the foundational element.

Only my soul again, a studio of paper. Forgive me: uncontrolled drum beats, guilty hand. My heart lengthens with the subtlest inflection. Look for it. Here.

I have not forgotten my mother. It is you, in all the somewhere surging forth from the criticism. The velvet is that ringing.

Poster the tick-tock and the glory.