In her 1652 literary salon, Madeleine de Scudery introduced the word “roman a clef” to describe a genre of writing that is autobiography overlaid with fiction. Now also called by various names including auto-fiction, nonfiction novel, autobiographical novel, etc.

“So ask me again now—what is autobiographical about my novel—and I will talk about fidelity to emotional effect and contextual variance. About level shifts and category shifts and the impossibility of exact equivalencies. I might discuss the translatability of the source material and then take you through the reconstruction of sound or image or structure. I will mention how inner becomes outer, how sometimes all you can do is convey meaning or form but not both. I will talk about the tension in word choice and metaphor, the gift of plenty and the risk of nuance. I will invite you to wend with me, to wander through the words. Because I am always in the work and outside of it. I am and am not the story.”

- Michelle Bailait-Jones, “On the Impossibility of Locating the Line Between Fiction and Non” (LitHub)

Example of nonfiction novel: Amitava Kumar’s Immigrant, Montana.

Multiple epigraphs, pictures, footnotes (academic and digressive), references to pop culture, explications of literary theory. Stories structured by associative leaps and hops from digression to digression. Dedicated to Teju Cole, whose style inspired it.

Kailash uses two voices to tell his story. There is his older self, speaking from twenty years’ distance with the help of his journals and notebooks, and then there is his guiltier, younger self. That’s the voice that the newly arrived, inauthentic-feeling Kailash uses to address an imaginary judge who wants to kick him out of the country.

- Joanna Biggs, “Erotic Exploration in Immigrant, Montana” (New Yorker)

Kumar explains early and forcefully why these subjects—geopolitics and sex; geography and desire; history and lust—should share pages. In an enormously funny yet simultaneously dark recurring device recalling Roth’s Portnoy addressing his psychiatrist, Kailash speaks to an imagined immigration judge whom he pictures adjudicating both his status in America and his libidinous proclivities. Sex, Kailash tells us, is the “crucial part of humanity denied to the immigrant. You look at a dark immigrant in that long line at JFK…you look at him and think that he wants your job and not that he just wants to get laid.”

-Sanjena Sathian, “Geopolitics and Sex, Geography and Desire: On Amitava Kumar’s ‘Immigrant, Montana’" (The Millions)

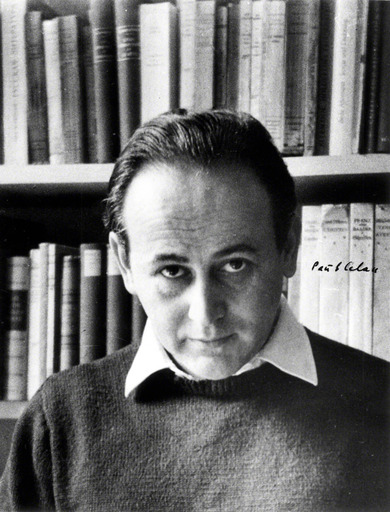

Teju Cole: “To be a writer in exile is a great thing. But what is exile now, when everyone goes and comes freely?”

Ben Lerner and Sheila Heti practice an auto-fiction in which the book turns in to the self while Alice Sebold and Teju Cole write novels that turn to the world.

The difference between fiction and memoir may be the difference—when it comes to meaning, that recyclable plastic thing we crave in our lives, and without which we become despondent and ultimately inert—between metaphor and referential mania. They say the truth shall set you free, but it seems rather to be the case that fiction, or, Stories About Fake People, who can be understood by means of the empathic engine of metaphor to be yourself, shall free you from that intolerable freedom we call meaninglessness.

- Rebecca Wolff, “Our Sense of Truth” (Lithub)

Phillip Roth’s view of selfhood as perpetual performance with a character in a book being only one variant of that enormous possibility.

“People constantly change their story… we are writing fictitious versions of our lives all the time, contradictory but mutually entangling stories that, however subtly or grossly falsified, constitute our hold on reality and are the closest thing we have to truth.”

- William Gass quoting Phillip Roth, “Deciding to Do the Impossible” (New York Times)

Tim Parks on Leo Tolstoy’s use of life for fiction. After Anna Karenina, Tolstoy chose the performance of goodness and sainthood over the writing of fiction, which felt to him like an indulgence. His relationship with Sonya, his wife, and their thirteen children, kept him rooted in the flesh and the material. Then in 1887, Tolstoy returned to fiction to write The Kreutzer Sonata (my personal favorite novella), in which protagonist holds his views on abstinence and material world and kills his wife in a fit of rage when he discovers she is having an affair with the violin teacher. Six years later, Sonya fell involve with her younger piano teacher but Tolstoy did not kill her. It’s not clear whether he wrote the script for the affair or predicted it. A character is not a steady state so much as a tension between various poles and forces. The problem is being anyone at all.

“Let’s offer this formulation: a certain kind of writer, for whom the day-to-day performance of self—the interaction of personality with the world—is complex and conflicted, invents multiple fictional selves who deal with the same predicament in different ways. Rather than establishing any ultimate truth about identity, such a writer explores possibilities that might be dangerous or incompatible in real life. In short, the writing becomes an extension of the living.”

- Tim Parks, “How Best to Read Auto-Fiction” (New York Review of Books)

In “Corn Maze,” Pam Houston talks about the blurred lines between fiction and nonfiction. When she toured for her first fiction collection, Cowboys Are My Weakness, the question she was asked most often was how much of this really happened to her? She answered honestly: “A lot of it.”

Houston maintains that truth can never be an absolute. The instability of truth automatically locates creative nonfiction between genres.

“When it was decided (When was that again, and by whom?) that we were all supposed to choose between fiction and nonfiction, what was not taken into account was that for some of us truth can never be an absolute, that there can (at best) be only less true and more true and sometimes those two collapse inside each other like a Turducken. Given the failure of memory. Given the failure of language to mean. Given metaphor. Given metonymy. Given the ever-shifting junction of code and context. Given the twenty-five people who saw the same car accident. Given our denial. Given our longings. // Who cares really if she hung herself or slit her wrists when what really matters is that James Frey is secretly afraid that he’s the one who killed her.”

The line of acceptable imagining in blurry. Houston gives example of three Italian kayakers which she loosely invented for an essay which the editor removed because they weren’t “real” in the sense of being verifiable. Maybe they were Spanish. On the other hand, the same editor added a fog to create atmosphere.

Her novel of 144 chapters does not purport to be nonfiction. And yet, as the James Frey scandal blew up, Pam Houston revisited her naming strategies.

“In past books I have used Millie, Lucy, and Rae. For the sake of sentence rhythm, I was leaning towards something with one syllable, but it would also be convenient to the book if the replacement name meant something as embarrassing as what the name “Pamela” means: which is all honey. I had considered Melinda, which on some sites means honey and could be shortened to Mel. I had considered Samantha which means listener, and could be shortened to Sam. But in the car with the elk in the pasture and the snow on the road and Jeff Tweedy in my ears I was all of a sudden very angry at whoever it was who put all that pressure on Oprah Winfrey. This book was in danger of missing the whole point of itself if my name were not Pam in it. If my name were not Pam in it, who was the organizing consciousness behind these 144 tiny miraculous coincident unrelated things?”

In naming characters for fiction, the conventions don’t always make sense. You can write fiction that resembles a real person more than the nonfiction that names them and proceeds carefully.

“Speaking only for myself, now, I cannot see any way that my subsequent well-being depends on whether or not, or how much, you believe what I am telling you—that is to say—on the difference (if there is any) between 82 and 100 percent true. My well-being (when and if it exists) resides in the gaps language leaves between myself and the corn maze, myself and the Las Vegas junkies, myself and the elk chest-deep in snow. It is there, in that white space of language’s limitation that I am allowed to touch everything, and it is in those moments of touching everything, that I am some version of free.”

Her writing tends to avoid didactic statements because she feels like she can’t speak for everyone.

“I have never felt comfortable speaking for anyone except myself. Maybe I had been socialized not to make declarative statements. Maybe I thought you had to be fifty before you knew anything about the world. Maybe I was afraid of misrepresenting someone I thought I understood but didn’t. Maybe I was afraid of acting hypocritically. Maybe I have always believed it is more honest, more direct, and ultimately more powerful, to tell a story, one concrete and particular detail at a time.”

And finally, in loose sum, a writing prompt of sorts from Alexander Chee’s essay, “The Writing Life,” found in How to Write An Autobiographical Novel: Essays:

“The writer Lorrie Moore calls the feeling I felt that day ‘the consolations of the mask,’ where you make a place that doesn’t exist in your own life for the life your life has no room for, the exiles of your memory.”