1. Transit papers

We don't talk about papers enough. This is because most Americans genuinely lack personal, lived experience with the absolutely mind-boggling labor, money, risk, and time involved in the procurement of visas and transit papers for stateless persons or refugees. As part of my ongoing commitment to consume every book ever published by NYRB, I read Anna Seghers’ novel, Transit, with great interest in its treatment of refugees and stateless persons.

The translation by Margot Bettauer Dembo—her final work of translation—is intimate, disturbing, and powerful. One feels alienation like a close houseguest, or a lost language, the lip of an inaccessible elsewhere.

Peter Conrad’s introduction ties Segher's novel to her lived experience as a Communist trying to escape Hitler's armies. She was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933; upon release, she fled to Paris, then to Marseilles, one of the few ports available to exit visas. (Seghers was Jewish, which certainly factored into the threat that Nazism posed to her life.) Conrad compares Seghers’ refugees to Kafka's Joseph K, seeking to get his credentials as a land surveyor recognized by the rulers of the castle.

In 1941, Seghers (and her family) procured permits to board a ship for Mexico—and she began to write this book immediately upon arrival. Like Marie, the novel's quasi-heroine, Seghers lived the in-between state of warring borders and expired papers. The novel offers few emotional characterizations to distinguish the characters, many of whom are refugees waiting for papers in Marseilles. In a sense, all details exist only to be demolished by the violence of the occupation, and by the quiet intersecting complicities of French citizens.

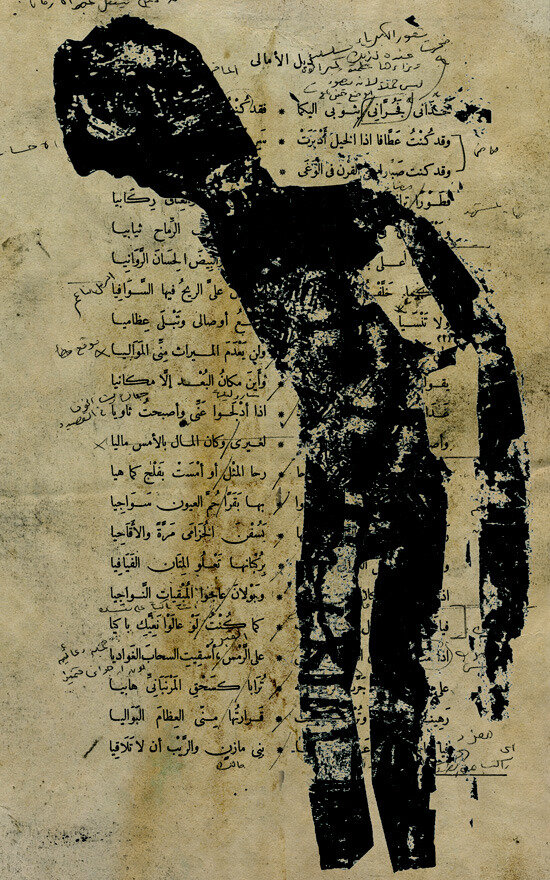

The male narrator of Transit doesn't even inhabit a name. He is among the nondescript nameless, seeking a future in the words of others, the moment by moment navigations. He has no distinguishing beliefs, looks, or ideologies. He begins with describing his time spent in work camps performing "labor service" by unloading British munitions ships, where he felt himself "in the shadow of death."

Ultimately, he escapes the Vichy regime by passing himself off as Weidel, a dead Jewish author whose suitcase he discovers in a hotel room. Along with Weidel’s papers, the suitcase also contains Weidel’s final manuscript. By some twist of fate, the narrator happens to have fallen in love with the Weidel’s girlfriend, who does not yet know that he is dead—and who is trying to find him so that her transit papers can be finished.

For the narrator to steal a dead’s man identity is hardly a crime in a time when survival depends on anonymity. And the whole novel is retrospective: a confession recounted by the narrator to an American border official for whom such stories are thrilling, museum-like, and incomprehensible.

2. The Struma and Mihail Sebastian

The first lines of Transit:

"They're saying that the Montreal went down before Dakar and Martinique. That she ran into a mine."

Immediately, I thought of Mihail Sebastian's diary, where he expresses anxiety and concern over what would later be called the Struma disaster. The Struma was a small ship commissioned to carry nearly 800 Jewish refugees from Axis-allied Romania to Palestine. Sebastian attempts to navigate between conflicting media reports: whether the ship carrying Romanian Jewish refugees arrived safely, or whether it had been sunk.

Over one hundred pages of Sebastian’s diary reference the absolutely abysmal media reporting and propaganda, and the paralyzing effect this had on Jewish persons in determining whether to flee or “wait for it to pass.” The Struma disaster would later be referenced by Romanian Jews as why some chose to flee by foot or stay put, rather than try a boat.

Here’s the Wikipedia version of what happened:

Struma's diesel engine failed several times between her departure from Constanţa on the Black Sea on 12 December 1941 and her arrival in Istanbul on 15 December. She had to be towed by a tug boat to leave Constanţa and to enter Istanbul. On 23 February 1942, with her engine still inoperable and her refugee passengers aboard, Turkish authorities towed Struma from Istanbul through the Bosphorus out to the coast of Şile in North Istanbul. Within hours, in the morning of 24 February, the Soviet submarine Shch-213 torpedoed her, killing an estimated 781 refugees plus 10 crew, making it the Black Sea's largest exclusively civilian naval disaster of World War II. Until recently the number of victims had been estimated at 768, but the current figure is the result of a recent study of six different passenger lists. Only one person aboard, 19-year-old David Stoliar, survived (he died in 2014).

3. Walter Benjamin and Weidel

Weidel's manuscript suitcase, for me, maps upon the missing suitcase of Walter Benjamin—and with it, the possibility that someone used it to publish his text.

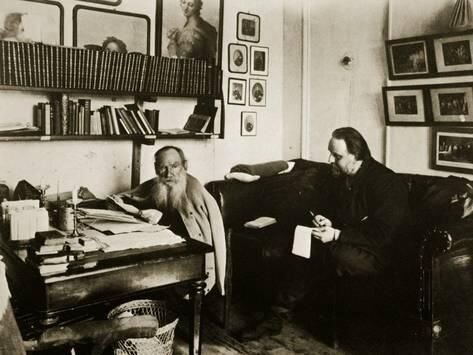

I thought about this as I traced relations between Seghers and Benjamin during their Paris days. Both wrote within a climate of rising fascism. Where Benjamin's reproduction of news headlines and local ephemera offered the landmarks of rising fascism, Seghers' narrator speaks from a blurred, distracted distance, evoking a world where moral boundaries have become as fuzzed and non-commital as those of nation-states.

In 1937 and 1937, Benjamin was seeing more of Seghers (born Netty Reiling, 1900), who was already known as a novelist (her first book was published in 1928) and activist. And he probably knew Seghers through her husband, László Radványi, a Jewish Hungarian writer and poet who had been involved in the revolution which created the Hungarian Soviet Republic—and who was forced to flee when the HSR was disbanded in 1919. Radványi fled to Vienna, where he acquired the pseudonym "Johann Lorenz Schmidt" (from the 18th-century Protestant dissident theologian). In 1923, he got his doctorate in philosophy from Heidelberg University, where his these on Chialism was directed by Karl Jaspers.

In Heidelberg, Radványi/Schmidt met poet Anna Seghers. They married in 1925 and had two children, Pierre and Ruth (pictured in portrait at the top).

Benjamin and Radványi had both been interned at La Varret. This is where they met, in a French internment camp. After Radványi was released from labor camps, he, Seghers, and their two children went to Marseilles, where they became part of the crowds trying to flee Vichy France. She fled via Mexico City to New York City, and returned to the German Democratic Republic in 1947, where she became a prominent figure.

Benjamin, on the other hand, joined a handful of others fleeing on foot towards the Spanish coast. After being refused transit at the Spanish border, Benjamin took his own life that night in a border hotel. His suitcase is still missing.

4. The Gide aside

In 1936, Andre Gide accepted an invitation to tour the Soviet Union, and his dreams of liberation crumbled like the plaster from Potemkin villages. In Return From the the USSR, Gide recanted his support for the Soviet project as it stood, which he believed to be antithetical to flourishing, human thriving, and queer comrades in general.

Gide was writing as a socialist, as someone committed to liberation—and so he framed his book by criticizing the particulars in the name of a hopeful, more liberated (and socialist) future:

I do not hide from myself the apparent advantage that hostile parties—those for whom "their love of order is indistinguishable from their partiality to tyrants"[1]—will try to derive from my book. And this would have prevented me from publishing it, from writing it, even, were not my conviction still firm and unshaken that, on the one hand, the Soviet Union will end by triumphing over the serious errors that I point out, on the other, and this is more important, that the particular errors of one country cannot suffice to compromise a cause which is international and universal. Falsehood, even that which consists in silence, may appear opportune, as may perseverance in falsehood, but it leaves far too dangerous weapons in the hands of the enemy, and truth, however painful, only wounds in order to cure.

In hindsight, it was a sort of bourgeois naivety that led Gide to believe his speech commemorating the death of Maxim Gorky could have been well-received by those present in Moscow’s Red Square, but we must take it on faith that Gide was idealist enough to celebrate how literature, the province of the leisured and wealthy, now belonged to the worker, or the silent masses:

I could not weary of contemplating the numbers of women, of children, of workers of all kinds for whom Maxim Gorki had been a spokesman and a friend. I reflected with sorrow that these people, in any other country than the U.S.S.R., belonged to those to whom entry of the hall would have been forbidden; to those who, precisely, when they come to the gardens of culture are confronted with a terrible "No admittance. Private property." And tears came to my eyes at the thought that what seemed to them already so natural seemed to me, the Westerner, still so extraordinary.

Gide goes on to contradict himself, claiming that great writers have always been revolutionaries (but also bourgeois, leisured, etc), and that the new problem for writers is being revolutionary while losing their status as rebels:

And it seemed to me that there existed here, in the Soviet Union, a most surprising novelty—up till now, in all the countries of the world, a great writer has always been, more or less, a revolutionary, a fighter. In a way that was more or less conscious and more or less veiled, he thought, he wrote, in opposition to something. He refused to approve. He brought into the minds and into the hearts of people the germs of insubordination, of revolt. Respectable people, public powers, the authorities, tradition, had they been far-seeing enough, would not have hesitated to recognize in him the enemy.

Today, in the U.S.S.R., for the first time, the question is put in a very different manner; while remaining a revolutionary, the writer is no longer a rebel. On the contrary, he responds to the wishes of the greatest number, of the whole people, and what is most remarkable, to those of the rulers. So that there appears to be a sort of fading away of the problem, or rather a transposition so new that at first it disconcerts thought. And it will not be one of the least glories of the U.S.S.R. and of those prodigious days which still continue to shake our old world, to have called up into fresh heavens new stars and unimagined problems.

If one hasn’t read Gide’s pamphlet, it’s a humorous historical dive inflected by Gide’s unique voice. The book caused a huge commotion among the European Left; many tongues clucked, others wagged, some stayed glued to the roofs of their mouths. I wouldn’t be surprised if CIA cash was used to help publish it.

5. Backtracking to 1937 intellectual climate

In continental Europe, political tensions over Madrid's fall to Franco's Nationalists made lip service support for the Republican cause in Spain verboten. It was a tense time. The Popular Front offered the single viable alternative to Nazi occupation.

Thus it comes as a surprise to find Walter Benjamin, in letters to friends, refusing to condemn Gide for throwing shade on the Soviet Union before actually reading the book. In 1937, Walter Benjamin was struggling to get eyeglasses, as his eyesight had worsened to the point where he was afraid to leave home. He was reading—and loving—Carl Juster Jachmann's On Language, which he called "meteoric" for its insight into the collision of language and politics. Jachmann's these that "the regression of poetry is the progress of culture" blamed Germany's failure to move towards a politics of liberation on its obsession with literature. Benjamin wrote an essay on Jachmann which he shared with Theodor Adorno in Paris in the spring of that year.

Also in the spring of 1937, Benjamin attends Anna Segher's speech honoring the work of Georg Büchner. Benjamin appreciates her speech, though he doesn’t say much about her poetry.

In the same month, Benjamin promises himself that he will pen a critique of Jungianism, whose "fascist armor" he swore to "expose." He sees Jung as offering a "clinical nihilism" which may have appealed to Celine, but which heralded a danger to free thought and expression.

In May 1937, Siegfried Kracauer published Orpheus in Paris: Jacques Offenbach and the Paris of His Time. The book used biography as a lens into the socio-cultural history of Second Empire Paris, aiming to be a "physiognomy" of a cultural era. Both Adorno and Benjamin bonded over their hatred of it, but it was Adorno who sustained a long-standing vendetta which resurfaced in his Minima Moralia, published in the 1950's. One must credit Adorno, perhaps, with a capacity for steadfast, unrelenting intellectual-grudge commitments.

By the summer of 1937, Benjamin expresses dismay in the Popular Front, writing "leftist majority pursues a politics with which the rightists would provoke revolts." The Stalinist show trials continue in Soviet Russia, which Benjamin finds worrisome.

“There is a view onto gloom through whatever window we look,” he wrote to Fritz Lieb, continuing:

“The destructive effect of events in Russia will inevitably continue to spread. And the bad thing about this is not the facile indignation of the staunch fighters for ‘freedom of thought’: what appears to me to be much sadder and much more inevitable at the same time is the silence of thinking individuals who, precisely as thinking individuals, would have difficulty in taking themselves for informed individuals. This is the case with me, and probably also with you.”

Back in Bucharest, Mihail Sebastian is watching the Iron Guard emerge as an ideological competitor. In December 1937, religious scholar Mircea Eliade is not yet teaching in a tenured position at the University of Chicago. He’s just another young intellectual who has fallen for the Legionary, fascist movement. Eliade will celebrate a few weeks later as Jews are forbidden to work in the journalism profession. He will celebrate as the fascists moved to erase Jewish voices from the national press. The silence of Jewish erasure will lack translators.

Sebastian’s 1938 journal begins with fake news, or its predecessor. The word propaganda hovers over the new uniforms, their ideologies, their apologists. In Bucharest, Sebastian will listen to his charismatic professor, Nae Ionescu, build a case for a mystical “National Greatness” that relies on exclusion of what is foreign. Ethics, for Nae, isn't a question of whether one should kill the enemy, The Foreigner, the Jew - but rather, whether one does this with relish rather than light regret.

To do the deed with one's mind is different from doing the deed with one's heart.

Sebastian will listen, add this to his notebooks, wondering at which point the illness of ideology will release his friends. And how much harm will be accomplished in the interim?

At a cafe, he and Bellu Zilber will discuss alternatives, or carve out the shadows of rising anti-Semitism in their own flesh. The maps are a question of survival—of what one must be, or become – in order to live. “The People” has become an altar demanding sacrifice; the political is sacralized in national greatness.

Should another People be constructed to oppose it? How many Peoples need to exist? Can Peoples co-exist? At the table, Sebastian sees humans, divided by hyphens, believing the bridge can carry them. Zilber suspects that only communist internationalism can save Jews from death in German camps. Sebastian believes multinationalism and fluidity offer eternal protection. Others believe the hope is in Zionism. Many are trying to get visas, exit permits, passports which enable them to leave the land where they were born, the land of their fathers and mothers.

Decades later, Bellu Zilber will sit in prison during the communist show trials, revisiting his commitments in light of changing allegiances. Now, The People have become The Party; internationalism is Trotskyism, an official crime against the Peoples’ Republics. Nationalist communism emerges to fill the vacuum of Stalinist and Soviet empire. But who can measure the distance between national interest and anti-Semitism in the dictators mouth? Sebastian will not live long enough to witness his friends’ silence in prison. If he had, one could hardly imagine his response.

* Eiland and Jennings, Walter Benjamin: A Critical Life, pp. 555-556, 567. Sebastian, 113.

![Cubas atop the donkey—though the muleteer is missing. From Mariana Rio’s illustrations for Memorias Póstumas de Brás Cubas published by Editorial Sexto Piso. [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5aea0d8696e76f6ac6f09e3c/1616020838918-CFGHQWYZQ4CI1RCFR42W/Screen+Shot+2021-03-17+at+5.39.48+PM.png)